Rhapsody in Green and Orange, Part 2

If John Murray Anderson had been on board from the get-go, and if production had begun promptly once Paul Whiteman was signed in October 1928, King of Jazz might have caught the crest of the studio-revue wave as talkies came in, instead of sinking in the undertow as the wave rolled out. At the very least, the picture’s astronomical costs would have been only a fraction of what they were — even with Technicolor and Herman Rosse’s spectacular sets (which won him an Oscar for 1929-30). That in turn would have made King of Jazz‘s profit threshold a lot lower; in all likelihood, the picture would have cost less and earned more. But such was not to be. King of Jazz’s big splash turned into a belly-flop, and it sank like a rock.

If John Murray Anderson had been on board from the get-go, and if production had begun promptly once Paul Whiteman was signed in October 1928, King of Jazz might have caught the crest of the studio-revue wave as talkies came in, instead of sinking in the undertow as the wave rolled out. At the very least, the picture’s astronomical costs would have been only a fraction of what they were — even with Technicolor and Herman Rosse’s spectacular sets (which won him an Oscar for 1929-30). That in turn would have made King of Jazz‘s profit threshold a lot lower; in all likelihood, the picture would have cost less and earned more. But such was not to be. King of Jazz’s big splash turned into a belly-flop, and it sank like a rock.

And that might have been the end of it, had it not been for something that almost nobody in 1930 foresaw: Bing Crosby became a star. In King of Jazz he got only seventh billing — and at that, not even by name, but as one of the Rhythm Boys (with Al Rinker and Harry Barris), the scat-singing piano and vocal trio that toured as members of Whiteman’s band. If anybody had been making predictions at the time, they probably would have picked Harry Barris as the one who was going places. But instead it was Bing, first on records, then radio, finally in movies with 1932’s The Big Broadcast at Paramount (where they wasted no time putting him under contract). He wasn’t yet the national institution he would become (and remain to his dying day), but he was definitely hot, and his popularity was a factor in Universal’s decision to reissue King of Jazz in June 1933. (Another factor was the return of musicals to audience favor in the wake of 42nd Street, Footlight Parade and Gold Diggers of 1933 over at Warner Bros.)

This reissue was a substantially different movie from the one audiences saw (or more often, didn’t see) in 1930. The order of the sequences was changed and the running time slashed from 104 minutes to 65. Production numbers were shortened, at least one whole song eliminated (“I’d Like to Do Things for You”, sung by pert little Jeanie Lang to Paul Whiteman, then reprised by William Kent and Grace Hayes, then again by the dance act Nell O’Day and the Tommy Atkins Sextet). All but one of the comedy blackouts were cut, while three that had been shot in 1930 but never used were added. Bing’s appearances with the Rhythm Boys were all retained, of course, and he was given star billing in a new set of opening credits.

Also substantially different had been the foreign market versions of King of Jazz that had played overseas during 1930 and ’31. The United Kingdom got the same picture as the U.S., but foreign language versions dispensed with all the comedy blackouts and added new introductions for the musical selections, shot with native-speaking hosts in Spanish, Czech, Hungarian (one of the hosts here was the as-yet-unknown Bela Lugosi), Swedish, Portuguese, German, Italian, French and Japanese.

So let’s recap: By the end of 1933, there had been a total of some 11 distinctly different versions of King of Jazz (or El Rey del Jazz, Král jazzu, Der Jazzkönig, La Féerie du Jazz, Kingu Obu Jazu, etc.) playing somewhere on the globe at one time or another. This confusing plethora of source material would present quite a challenge 80-plus years later, when NBCUniversal undertook to restore the picture in 2015.

So let’s recap: By the end of 1933, there had been a total of some 11 distinctly different versions of King of Jazz (or El Rey del Jazz, Král jazzu, Der Jazzkönig, La Féerie du Jazz, Kingu Obu Jazu, etc.) playing somewhere on the globe at one time or another. This confusing plethora of source material would present quite a challenge 80-plus years later, when NBCUniversal undertook to restore the picture in 2015.

But first would come decades of obscurity — partly because, while movie musicals managed to regain favor with audiences, revues never did, and partly because Technicolor’s perfecting of their three-strip process in 1934 rendered King of Jazz‘s two-strip Tech obsolete (and, in the eyes of the Technicolor Corp., a bit of an embarrassment). King of Jazz was never released on 16mm for non-theatrical markets, nor was it in any of the packages released to television — the customary routes for movies to find their way into the underground world of film collecting. Among movie buffs the picture gained the status of wistful legend, a movie that few could remember seeing, nobody could even guess at where or how to find, and only trivia connoisseurs had ever even heard of. By 1954, it was commonly assumed that nothing survived but the picture’s trailer.

Then in the 1960s bits and pieces began surfacing here and there, snippets unearthed at various archives and distribution centers. There was even a “reconstruction” in 1965 that managed to combine a mute copy of the image from the French La Féerie du Jazz with soundtrack discs from the Czech Král jazzu. That was no doubt a strange animal indeed — but it was the only King of Jazz anybody knew about.

That is, until a nearly-complete nitrate print surfaced in the late ’60s, a print whose origins are still a little cloudy. One story, probably apocryphal, claimed that it was found among Benito Mussolini’s effects after his execution in 1945, and it was known in some quarters as “the Mussolini print”. But that’s hardly likely; if Mussolini had anything, it surely would have been Il re de jazz.

In 1968, British broadcaster and film collector Philip Jenkinson gained access to this “Mussolini” print and made his own dupe negative from it, which he used to strike 16mm prints for discreet trading among collectors. As additional footage became available (and Jenkinson did have his connections), this version grew from 88 to 95 minutes by 1975.

Finally, long story short — again, pick up James Layton and David Pierce’s book for the full fascinating story — Universal licensed King of Jazz for selected festival screenings, and they made preservation elements from the original nitrate camera negative, which miraculously survived in the studio’s vault (albeit only in the 65 min. reissue version; cuts had been made in the original negative and all the trims discarded). The picture was released to cable TV in March 1983, and on VHS cassette later that year.

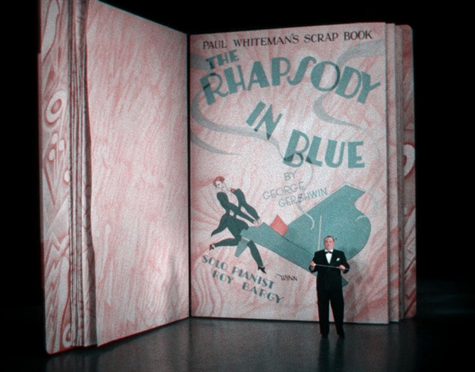

It’s this VHS version that has been in circulation for 33 years (never available on DVD except in various bootlegs), and on which my own fondness for King of Jazz has always rested. (The picture here, and the shot of the Russell Markert Girls in Part 1, are frame-caps from it.) Now I learn that this was (in Layton and Pierce’s words) “a bastardized version…a mishmash of the 1930 and 1933 releases compiled to create the longest possible cut.” And at that, it still runs only 91 minutes.

It’s this VHS version that has been in circulation for 33 years (never available on DVD except in various bootlegs), and on which my own fondness for King of Jazz has always rested. (The picture here, and the shot of the Russell Markert Girls in Part 1, are frame-caps from it.) Now I learn that this was (in Layton and Pierce’s words) “a bastardized version…a mishmash of the 1930 and 1933 releases compiled to create the longest possible cut.” And at that, it still runs only 91 minutes.

Worse, the Universal home video department, in a (possibly) well-intended but (definitely) misguided effort to make the color more natural-looking to modern audiences, tinkered with the two-strip Tech — e.g., cranking up the blue, a color to which the process was blind. You can see it in this picture.

(As an aside, this kind of thing was common in those early days of home video, though it never sparked the outrage that attended the colorizing of black-and-white movies, since people had nothing to compare it to. Case in point: Warner Bros.’ Mystery of the Wax Museum. That one was long believed lost until a 35mm nitrate print surfaced in 1969 — by some reports, in Jack L. Warner’s private collection. I saw that print projected in a Midnight Halloween screening at the San Francisco International Film Festival in 1970. The palette was limited, of course, but the color was delicately gorgeous, a far cry from the pallid, harsh, high-contrast image on every video release I’ve ever seen. Those releases all derive from the print I saw, the only one in existence, and I’m here to tell you they’re all absolutely wrong.)

The source material used for that VHS release of King of Jazz was highly variable, and some of it was pretty badly battered, with high contrast and washed-out color. In restoring the picture, NBCUniversal reviewed 16 different surviving picture elements of varying lengths, ultimately using four of them and coordinating with a complete 104 minute copy of the original soundtrack. I was going to scan some of the images from the restoration (as published in Layton and Pierce’s book) and post them here with frame-caps from the VHS for comparison, but there’s an even more dramatic demonstration available at the Two-Strip Technicolor site on Tumblr. Click on the link to see before-and-after crossfades from the VHS to the digital restoration (including the image immediately above).

Seen today — and I speak, of course, from familiarity with the “bastardized” VHS release — King of Jazz remains an embarrassment of riches. Some, admittedly, are richer than others, while some are chiefly of historical interest as examples of the kind of comedy and novelty performances that died with vaudeville. Several of the more impressive set pieces — for example, “My Bridal Veil”, a pageant of wedding attire from different historical eras from the 1550s to the 1920s, and “Rhapsody in Blue” itself — are film versions of shows John Murray Anderson staged for Paramount Publix Theatres. As such, they are of keen interest to those of us who know about such prologues only from what we can see in Footlight Parade. To see these extravaganzas in the flesh must really have been a knockout; to see them now in Technicolor is a real trip in the time machine.

Seen today — and I speak, of course, from familiarity with the “bastardized” VHS release — King of Jazz remains an embarrassment of riches. Some, admittedly, are richer than others, while some are chiefly of historical interest as examples of the kind of comedy and novelty performances that died with vaudeville. Several of the more impressive set pieces — for example, “My Bridal Veil”, a pageant of wedding attire from different historical eras from the 1550s to the 1920s, and “Rhapsody in Blue” itself — are film versions of shows John Murray Anderson staged for Paramount Publix Theatres. As such, they are of keen interest to those of us who know about such prologues only from what we can see in Footlight Parade. To see these extravaganzas in the flesh must really have been a knockout; to see them now in Technicolor is a real trip in the time machine.

It must be said that the movie gives short shrift to the African American contribution to the birth and development of true jazz — a contribution that was, of course, commanding, overwhelming and absolutely dominant. In the picture’s spectacular finale, “The Melting Pot of Music”, the roots of American popular music are traced to influences from England, Italy, Scotland, Germany, Ireland, Spain, Russia, and France. Conspicuous by their absence are elements from anywhere other than the continent of Europe — nothing from Africa, Asia, the Caribbean or Native America. But King of Jazz is a product of its time, and it never pretends to be an analytical documentary. It’s best that we judge not, lest we be judged and found wanting 90 years hence. Within the limits of its day and time, King of Jazz is a sumptuous spectacle and an impressive achievement.

Made even more impressive, one trusts and evidence suggests, in the new digital restoration so lovingly chronicled in King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue. As restored, the picture now runs 99 minutes; a few minutes, alas, seem irretrievably lost. Selected screenings are being scheduled worldwide, and a Blu-ray release must surely be on the table at some point. If you happen to be within driving distance of Cinedrome’s home in Sacramento, California, you may be in luck: A screening is tentatively scheduled (awaiting signing of contracts) for February 22, 2017 at Sacramento’s Tower Theatre, as a benefit for the Sacramento Traditional Jazz Society. Personally, I’m counting the days; I can hardly wait to finally see this movie I’ve always liked so much. (UPDATE 12/3/16: The February 22 screening at the Tower Theatre is now confirmed. There will be one showing only, and tickets should become available around January 1. Watch this space for further details. — jl)