Cinerama-Rama!

I had hoped to be able to go into more depth with this post, but events have overtaken me, so I have to write it pretty much off the top of my head and get it up as soon as possible.

It’s been, oh, 25 or 30 years now since a teenage cousin of mine heard me mention Cinerama and asked me what it was. I was astonished, back then, that there was someone who didn’t know. Well, that cousin is now 46, with a Ph.D. and a position in the Microbiology Dept. at the Univeristy of California Irvine. How many have been born since then who also don’t know what Cinerama was?

In a nutshell, and for the benefit of those who don’t know, Cinerama was the first successful widescreen process. Hollywood had flirted with widescreen photography in the late 1920s and early ’30s, but it proved to be an innovation too far for an industry already grappling with the transition to sound and the Great Depression, and the experiment quickly petered out in failure.

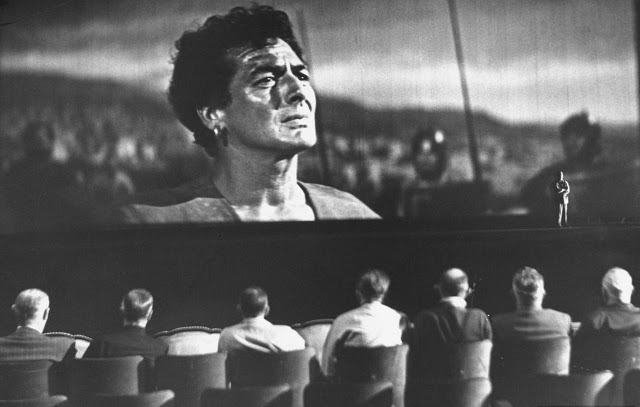

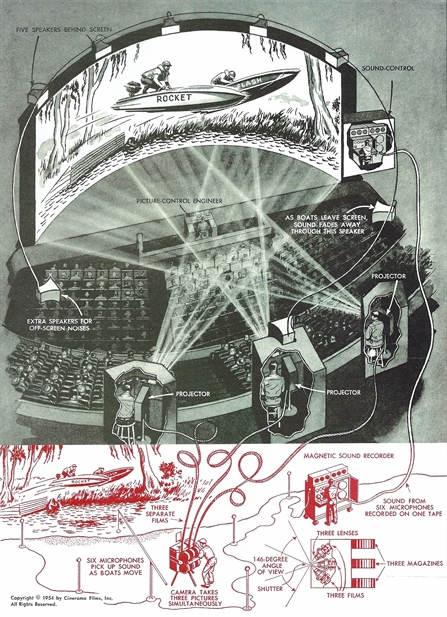

By the early ’50s things had changed — and besides, Cinerama was as different from those early pictures in Grandeur and Magnascope as FM radio was from AM. The screen wasn’t just wide, it was vast, curved 146 degrees to match almost the full range of human vision, using three synchronized projectors to display an image nearly five times the size of even the largest theater screen. And Cinerama had a multi-channel high-fidelity sound system for which a new term was coined: “stereophonic sound”.

By the early ’50s things had changed — and besides, Cinerama was as different from those early pictures in Grandeur and Magnascope as FM radio was from AM. The screen wasn’t just wide, it was vast, curved 146 degrees to match almost the full range of human vision, using three synchronized projectors to display an image nearly five times the size of even the largest theater screen. And Cinerama had a multi-channel high-fidelity sound system for which a new term was coined: “stereophonic sound”.

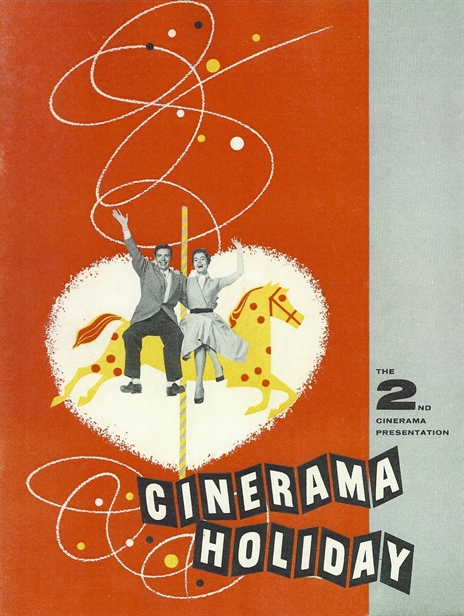

This coming September 30 will mark the 60th anniversary of Cinerama‘s premiere, and the occasion is not going unobserved. ArcLight Cinemas, which owns the Pacific Cinerama Dome in Hollywood (one of only three theaters in the world equipped to show true Cinerama) will be spending a week, from September 28 to October 4, presenting — to borrow the title of the second Cinerama production — a Cinerama Holiday. Every single Cinerama picture produced during the years Cinerama reigned as the Metropolitan Opera of movies will be on display, along with a couple of ringers — Cinerama’s Russian Adventure, an Americanized release of a picture produced by the Soviets in 1958 with pirated equipment and called Kinopanorama (then, typically of the time, the Russians accused us of stealing it from them); and Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich (1958), produced in a competing but compatible process called Cinemiracle — plus two movies that bore the Cinerama name even though they weren’t: It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (’64) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (’68).

This coming September 30 will mark the 60th anniversary of Cinerama‘s premiere, and the occasion is not going unobserved. ArcLight Cinemas, which owns the Pacific Cinerama Dome in Hollywood (one of only three theaters in the world equipped to show true Cinerama) will be spending a week, from September 28 to October 4, presenting — to borrow the title of the second Cinerama production — a Cinerama Holiday. Every single Cinerama picture produced during the years Cinerama reigned as the Metropolitan Opera of movies will be on display, along with a couple of ringers — Cinerama’s Russian Adventure, an Americanized release of a picture produced by the Soviets in 1958 with pirated equipment and called Kinopanorama (then, typically of the time, the Russians accused us of stealing it from them); and Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich (1958), produced in a competing but compatible process called Cinemiracle — plus two movies that bore the Cinerama name even though they weren’t: It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (’64) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (’68).

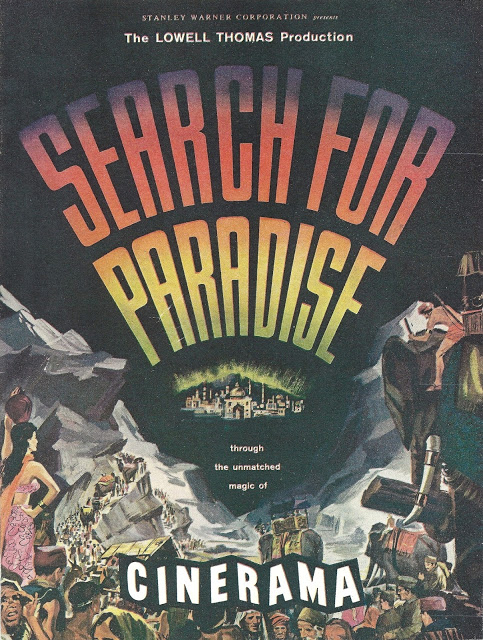

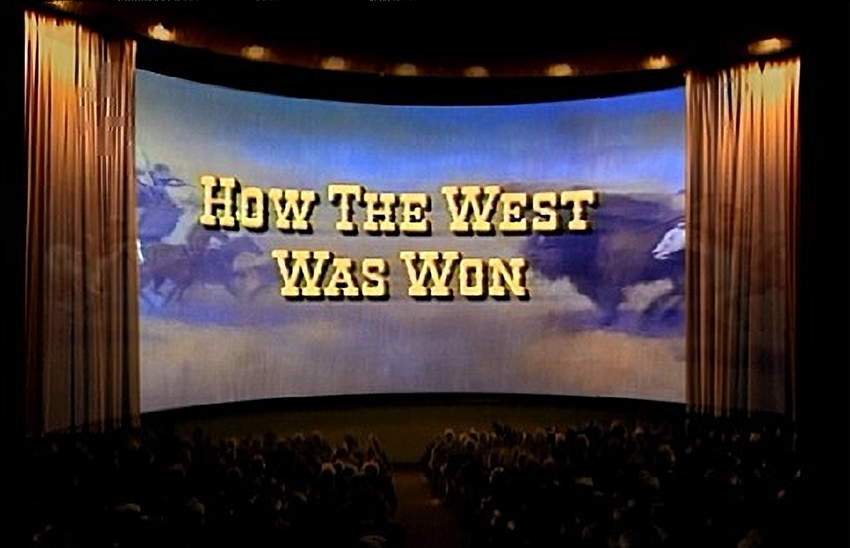

Not all the screenings will be in “classic” Cinerama. Two of the early travelogues (This Is Cinerama and Search for Paradise [’57]) and the two “story” productions (The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm and How the West Was Won, both ’62) will be screened in their original three-strip (i.e., three-projector) form, albeit with digital sound reproduction to replace the original console that played Reeves’s seven-track magnetic sound strip. Mad, Mad World will be shown in Ultra Panavision, the 70mm process that supplanted (but could never replace) Cinerama after How the West Was Won. The others will all be digital presentations, most of them remastered from original negatives.

I’m not sure what to expect from those digital prints, but I’m willing take a chance. In any case, the trip down to Hollywood will be worth it to see This Is Cinerama and How the West Was Won again, and Search for Paradise and Brothers Grimm for the first time. If you can possibly make it to Hollywood, you’ll find it worth the trip too. Click here for details and to purchase tickets (at this writing, only the first screening of each title is available for purchase; later screenings will no doubt be along in time).

I’ll have more to say about Cinerama, but I want to get this post up as quickly as possible. Tickets have only been on sale since Thursday, and they’re already going fast.

To be continued…

The Shout Heard Round the World

It was Merian C. Cooper who came up with the perfect way to introduce Cinerama to audiences. To do it he took a cue from his alter ego Carl Denham in his most famous picture, King Kong, and the way Denham introduced the giant ape to New York.

Spectators at that first showing on September 30, 1952 walked into an auditorium dominated by a huge curved wall of wine-red curtains. As the house lights dimmed, they heard the Morse Code dit-dit-ditting that was familiar to them all as the intro to Lowell Thomas’s daily radio program. The red curtains parted slightly, and there was the image of Thomas himself, in black and white, on a standard-size movie screen, welcoming them.

Spectators at that first showing on September 30, 1952 walked into an auditorium dominated by a huge curved wall of wine-red curtains. As the house lights dimmed, they heard the Morse Code dit-dit-ditting that was familiar to them all as the intro to Lowell Thomas’s daily radio program. The red curtains parted slightly, and there was the image of Thomas himself, in black and white, on a standard-size movie screen, welcoming them.

Thomas promised the audience “the latest development in the magic of light and sound.” Then for a full 13 minutes Thomas reviewed the history of moving pictures, from The Great Train Robbery down to 1952. Finally: “The pictures you are now going to see have no plot. They have no stars. This is not a stageplay, nor is it a feature picture, nor a travelogue, nor a symphonic concert, nor an opera. But it is a combination of all of them. In fact, it is the first public demonstration of an entirely new medium. Ladies and gentlemen…This…is Cinerama!”

The curtains rolled open — rolled and rolled and rolled — to the sound of a thundering fanfare that might have accompanied a triumphant army’s march into Ancient Rome, augmented by gasps and squeals from the flabbergasted audience. The screen dissolved from that ordinary little black-and-white image of Lowell Thomas…

…and that Broadway Theatre audience was taken on an uninterrupted ride in the front seat of the Atom Smasher Rollercoaster at Rockaway, Long Island’s Playland amusement park. “No human being had ever sat in a theater and had this kind of visceral experience,” recalled production manager Jim Morrison. “It hit you right in the gut, right smack in the belly.” And historian Kevin Brownlow: “There was nothing to beat that moment… Suddenly the cinema seemed to open out…the back wall seemed to disappear and we were plunging on a rollercoaster. It was the most staggering moment one could possibly have.”

My own father’s reaction was more succinct. My uncle took him, my mother and my grandparents to see This Is Cinerama when it opened at San Francisco’s Orpheum Theatre on Christmas Day 1953. As the curtains opened and the rollercoaster burst into view, my father reared back in his seat, his eyes bulging from their sockets, and bellowed at the top of his lungs: “Jeeee-zuss Christ!!” He may have been more vociferous than anyone else that day, but every single person in the Orpheum had exactly the same reaction. I know because when my own turn to see This Is Cinerama came 11 years later — even after a decade of CinemaScope, Todd-AO, Panavision, VistaVision, and all the other scopes and visions Cinerama had inspired — that Great Unveiling had lost none of its power. No two ways about it, this was — and remains — the greatest knockout punch in the history of motion pictures.

My own father’s reaction was more succinct. My uncle took him, my mother and my grandparents to see This Is Cinerama when it opened at San Francisco’s Orpheum Theatre on Christmas Day 1953. As the curtains opened and the rollercoaster burst into view, my father reared back in his seat, his eyes bulging from their sockets, and bellowed at the top of his lungs: “Jeeee-zuss Christ!!” He may have been more vociferous than anyone else that day, but every single person in the Orpheum had exactly the same reaction. I know because when my own turn to see This Is Cinerama came 11 years later — even after a decade of CinemaScope, Todd-AO, Panavision, VistaVision, and all the other scopes and visions Cinerama had inspired — that Great Unveiling had lost none of its power. No two ways about it, this was — and remains — the greatest knockout punch in the history of motion pictures.

But more of that next time…

Ups and Downs of the Rollercoaster, Part 1

If there were such thing as a Dictionary of Stereotypical Characters, the entry for “eccentric inventor” would have a picture of Fred Waller. In the 1920s and ’30s, Waller’s day job was at Paramount’s East Coast studios in Astoria, Long Island, where he worked as a photographic jack of all trades. In one capacity or another he worked on, among other pictures, Male and Female (1921) for Cecil B. DeMille, and That Royle Girl (’25) and The Sorrows of Satan (’26) for D. W. Griffith. In the ’30s he produced and directed a series of innovative and visually striking jazz-flavored shorts featuring the likes of Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington and Fats Waller.

If there were such thing as a Dictionary of Stereotypical Characters, the entry for “eccentric inventor” would have a picture of Fred Waller. In the 1920s and ’30s, Waller’s day job was at Paramount’s East Coast studios in Astoria, Long Island, where he worked as a photographic jack of all trades. In one capacity or another he worked on, among other pictures, Male and Female (1921) for Cecil B. DeMille, and That Royle Girl (’25) and The Sorrows of Satan (’26) for D. W. Griffith. In the ’30s he produced and directed a series of innovative and visually striking jazz-flavored shorts featuring the likes of Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington and Fats Waller.

Meanwhile, on his own time, he tinkered and puttered. He invented a container for keeping food dry in humid climates, a remote-recording wind direction-and-velocity indicator, an adjustable sail batten for sailboats, and a still camera that could take a 360-degree panoramic picture. (Also, as I mentioned before, water skis, which he marketed as Dolphin Awkwa-Skees.) Through it all he continued his obsession with finding a way to photograph the full range of human vision, pursuing his idea that peripheral vision was as important to depth perception as binocular vision. He used to walk around his home wearing a baseball cap with toothpicks stuck in the brim, testing how far back he could place the toothpicks and still see them, mulling over the kind of screen he would need for what he had in mind.

In 1938, architect Ralph Walker came to Waller with a unique photography challenge connected with an exhibit Walker was designing for the petroleum industry for the upcoming New York World’s Fair. Walker envisioned a spherical room with a battery of projectors casting a constant stream of moving pictures, an idea that dovetailed neatly with what Waller had been turning over in his own head. With Walker’s firm, Waller formed the Vitarama Corporation, and by early 1939 he had a working model of eleven 16mm projectors showing a patchwork image on a concave quarter-dome screen suspended over the heads of the audience.

In 1938, architect Ralph Walker came to Waller with a unique photography challenge connected with an exhibit Walker was designing for the petroleum industry for the upcoming New York World’s Fair. Walker envisioned a spherical room with a battery of projectors casting a constant stream of moving pictures, an idea that dovetailed neatly with what Waller had been turning over in his own head. With Walker’s firm, Waller formed the Vitarama Corporation, and by early 1939 he had a working model of eleven 16mm projectors showing a patchwork image on a concave quarter-dome screen suspended over the heads of the audience.

In the end Walker’s clients, the representatives of the petroleum industry, decided not to use Waller’s Vitarama, opting for something simpler, more conventional — and, not incidentally, cheaper to produce and exhibit. Waller adapted the Vitarama idea for another exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair, a huge mosaic slide show of still images for the Eastman Kodak exhibit. More important, the idea of the concave screen had solved Waller’s dilemma over how to project his multi-part images to envelop an audience.

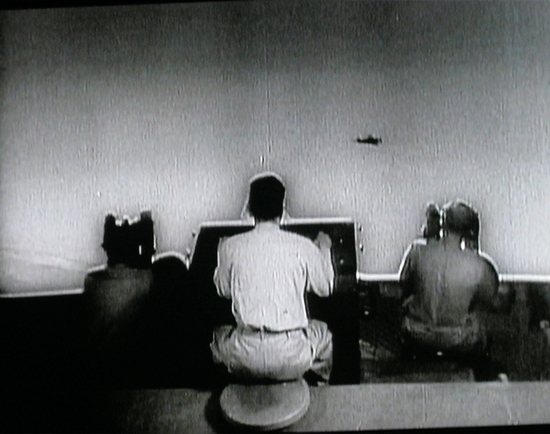

With a massive influx of military money (Waller later estimated it at over $5 million), the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer was born. It simplified the Vitarama design, using five 35mm projectors to display the same size image as the eleven 16mm ones, and it enabled Waller to work out the technical challenges involved in both the process itself and the manufacture of the equipment. Eventually 75 trainers, each occupying an area of some 27,000 cubic feet, were set up all over the U.S., in Hawaii, and in England, where over a million men were trained; the Air Force estimated that more than 250,000 casualties were averted thanks to this training.

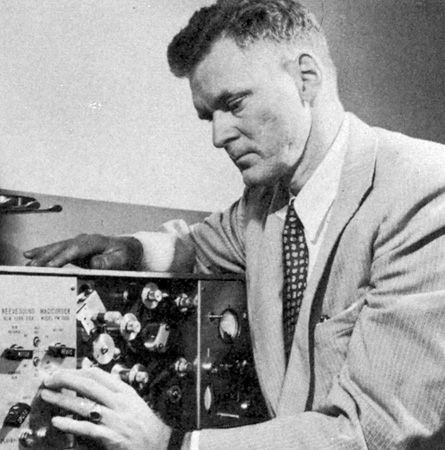

With a massive influx of military money (Waller later estimated it at over $5 million), the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer was born. It simplified the Vitarama design, using five 35mm projectors to display the same size image as the eleven 16mm ones, and it enabled Waller to work out the technical challenges involved in both the process itself and the manufacture of the equipment. Eventually 75 trainers, each occupying an area of some 27,000 cubic feet, were set up all over the U.S., in Hawaii, and in England, where over a million men were trained; the Air Force estimated that more than 250,000 casualties were averted thanks to this training. Also coming aboard at this time was Hazard E. “Buz” Reeves, one of the most brilliant and inventive men in the history of sound recording. Reeves had seen Vitarama as early as 1940, and was excited at the prospect of developing a sound system to go with it. Reeves and his company, Reeves Soundcraft, pioneered the use of magnetic recording for movies, a method more versatile than the standard practice of optical sound recording.

Also coming aboard at this time was Hazard E. “Buz” Reeves, one of the most brilliant and inventive men in the history of sound recording. Reeves had seen Vitarama as early as 1940, and was excited at the prospect of developing a sound system to go with it. Reeves and his company, Reeves Soundcraft, pioneered the use of magnetic recording for movies, a method more versatile than the standard practice of optical sound recording.

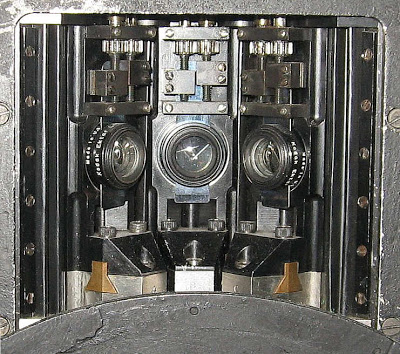

As Waller simplified the Vitarama/Cinerama process from five projectors to three, and from the quarter-dome screen to a wide curved rectangle (like the inner surface of a slightly flattened cylinder), Reeves developed a sound system to match: five huge loudspeakers behind the screen, each with its own discrete track, and a sixth track dispersed as needed to speakers placed at the rear and sides of the auditorium. (A seventh track, a composite of the other six, was intended only as an emergency backup and seldom used in practice.) Naturally, seven separate magnetic soundtracks required far more space than a standard optical soundtrack, so the sound was recorded on its own strip of 35mm film and run on a separate “projector” synchronized with the three image projectors just as they were synchronized with one another.

To be continued…

(PLEASE NOTE: For much of the information in this and following posts, I am indebted to the work of Dr. Thomas E. Erffmeyer, who wrote a history of Cinerama as his Ph.D. dissertation in Radio, Television and Film at Northwestern University [June 1985].)

Ups and Downs of the Rollercoaster, Part 2

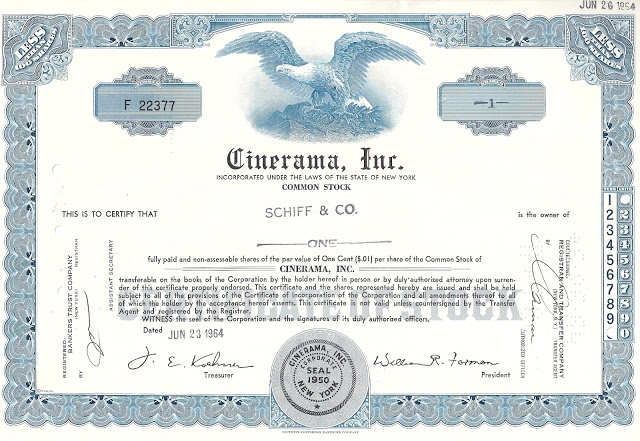

When Rockefeller and Luce bailed on Cinerama in July 1950, those other East Coast investors decided to take a pass as well, and Cinerama Corp. was dissolved in August. After buying out Rockefeller and Luce for a song, Hazard Reeves doubled down — he quite a bit more than doubled, in fact. In September he formed a new corporation, Cinerama Inc., in which Reeves Soundcraft was the principal stockholder, and set about tackling the challenges of moving Cinerama forward. The demonstration screenings at the converted tennis court continued. There were nibbles from independent producer Hal B. Wallis and a consortium of theater owners, but nothing came of them.

When Rockefeller and Luce bailed on Cinerama in July 1950, those other East Coast investors decided to take a pass as well, and Cinerama Corp. was dissolved in August. After buying out Rockefeller and Luce for a song, Hazard Reeves doubled down — he quite a bit more than doubled, in fact. In September he formed a new corporation, Cinerama Inc., in which Reeves Soundcraft was the principal stockholder, and set about tackling the challenges of moving Cinerama forward. The demonstration screenings at the converted tennis court continued. There were nibbles from independent producer Hal B. Wallis and a consortium of theater owners, but nothing came of them.

In the autumn of 1950 Cinerama got two big bites. Buz Reeves invited Lowell Thomas out to Oyster Bay to have a look; Thomas invited his business manager Frank M. Smith to come along, and Smith in turn invited another of his clients, theatrical producer Michael Todd.

It’s hard to explain Lowell Thomas to people who don’t remember him; even the Library of Congress was at a loss when it came time to classify his memoirs (they finally filed them under “biographies of subjects who don’t fit into any other category”). Born in 1892, he graduated from high school in 1910 and by 1912 (if we can believe Wikipedia) he had three bachelor’s degrees, plus an M.A. from the University of Denver. He worked as a reporter for the Chicago Journal, where he specialized in travel articles, which he expanded into lectures accompanied by motion pictures, thus pioneering (indeed, virtually inventing) the concept of travelogue movies. As a correspondent in the Middle East during World War I, he became world-famous for his coverage of the campaigns of T.E. Lawrence; subsequent lectures in New York and London spread the legend of Lawrence of Arabia. In 1930 he began 46 years of daily radio news broadcasts, first on NBC and later CBS, that made his resonant baritone one of the most familiar voices in America. His famous greeting (“Good evening, everybody.”) and sign-off (“So long until tomorrow.”) became the titles of his two volumes of autobiography. He wrote over 50 books in all, most of them chronicling his incessant world travels (the Society of American Travel Writers has an award named after him). When he became the voice of Fox Movietone News in the 1930s, it was he who lent stature to the newsreel, not the other way around. By 1950 he was one of the most respected men in American media.

Mike Todd (born Avrom Goldbogen in 1909) was also one of a kind, but a lot easier to classify. He was a flamboyant, dynamic showman cast in the mold of P.T. Barnum, mixing the high-rolling pretensions of a Florenz Ziegfeld or Billy Rose with the bumptious chutzpah of a Texas oil wildcatter. “A producer is a guy who puts on shows he likes,” he once said. “A showman is a guy who puts on shows he thinks the public likes. I like to think I’m a showman.” Among the shows with which he sought to please the public were Cole Porter’s Something for the Boys with Ethel Merman; The Hot Mikado, Gilbert and Sullivan in swingtime with an African American cast headed by Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, which opened on Broadway then transferred to the 1939 New York World’s Fair; The G.I. Hamlet with Maurice Evans; and Michael Todd’s Peep Show, a burlesque revue starring stripper Lilly “The Cat Girl” Christine — which, to Todd’s delight, was threatened with closure by censors in Philadelphia. Todd was adept at sweet-talking talent into his shows and even more adept at getting other men to foot the bill. He swung from fortune to bankruptcy and back with the regularity of a pendulum in a planetarium. As his son Mike Jr. remembered, when Todd saw Waller’s demonstration of Cinerama, he turned to an underling and gushed, “This is the greatest thing since penicillin! We’ve gotta get control of it!” (In fact, he never did — but I’ll get to that in its time.)

Lowell Thomas and Michael Todd had little in common beyond an instinct for showmanship and a flair for self-promotion, but they shared an avid enthusiasm for what they saw out in Oyster Bay. They also shared a business manager, Frank Smith, and that was enough for Smith to set up Thomas-Todd Productions Inc., licensed by Cinerama Inc. to produce and exhibit Cinerama movies. Thomas and Smith put up most of the money; Todd got stock in the corporation but, not surprisingly, didn’t put up any of his own money — his main contribution was to be his talent as a showman. In a parallel development, Cinerama Inc. had its initial public offering on the New York Stock Exchange in January 1951.

Also in early 1951 Thomas-Todd, or so the story goes, approached documentary master Robert Flaherty to direct the first Cinerama picture. Flaherty reportedly agreed, but he died in July ’51 as shooting was about to begin, leaving behind no notes or records to indicate what, if anything, he intended to do with Fred Waller’s process. This put Thomas and Todd back at square one.

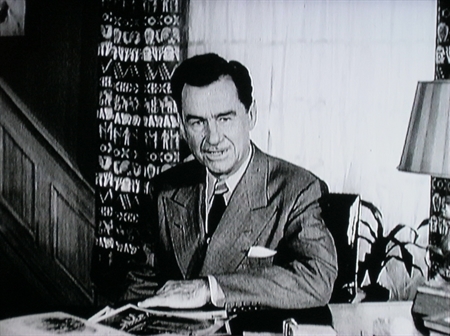

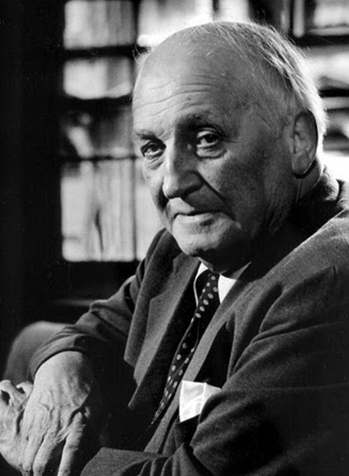

Also in early 1951 Thomas-Todd, or so the story goes, approached documentary master Robert Flaherty to direct the first Cinerama picture. Flaherty reportedly agreed, but he died in July ’51 as shooting was about to begin, leaving behind no notes or records to indicate what, if anything, he intended to do with Fred Waller’s process. This put Thomas and Todd back at square one. When all this footage was edited together in late 1951, it became clear that there wasn’t enough to make a full feature picture, so Thomas invited his friend Merian C. Cooper to come aboard. Even today, Cooper’s most famous production remains the original King Kong, but he has other ornaments on his résumé too: he was an early investor in the Technicolor process, and he partnered with John Ford on several of the director’s classic films: Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (’49), Wagon Master and Rio Grande (both ’50), with The Quiet Man (’52) and The Searchers (’56) still to come. Cooper had known Fred Waller in the early days at Paramount, and with that instinct for innovative ideas that made him an early passenger on the Technicolor bandwagon, he’d been following the industry buzz about Waller’s experiments out on Long Island. Cooper biographer Mark Cotta Vaz even suggests that Cooper may have approached Thomas before Thomas approached him: “He was convinced the picture business was in a rut and needed a good shaking up — and Cinerama was just the ticket.”

When all this footage was edited together in late 1951, it became clear that there wasn’t enough to make a full feature picture, so Thomas invited his friend Merian C. Cooper to come aboard. Even today, Cooper’s most famous production remains the original King Kong, but he has other ornaments on his résumé too: he was an early investor in the Technicolor process, and he partnered with John Ford on several of the director’s classic films: Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (’49), Wagon Master and Rio Grande (both ’50), with The Quiet Man (’52) and The Searchers (’56) still to come. Cooper had known Fred Waller in the early days at Paramount, and with that instinct for innovative ideas that made him an early passenger on the Technicolor bandwagon, he’d been following the industry buzz about Waller’s experiments out on Long Island. Cooper biographer Mark Cotta Vaz even suggests that Cooper may have approached Thomas before Thomas approached him: “He was convinced the picture business was in a rut and needed a good shaking up — and Cinerama was just the ticket.” In any case, there was an ulterior motive in enlisting Cooper: Mike Todd’s presence was becoming increasingly problematic. His domineering bull-in-a-china-shop style was beginning to grate on people. More important, perhaps, Todd’s presence spooked Wall Street. Thomas-Todd Productions wasn’t publicly held, but Cinerama Inc. was, and Todd’s well-known profligacy with other people’s money made investors wary. Then again, there were some ominous attempts by creditors from Todd’s numerous bankruptcies to recoup their losses from one of the Cinerama companies. There seemed nothing for it but to squeeze Todd out. By March 1952 it was announced he’d be taking a “leave” from Thomas-Todd Productions and Cinerama, and in August Thomas-Todd was dissolved, replaced by Cinerama Productions Corporation, with Lowell Thomas as chairman of the board.

Mike Todd’s 14 months on the scene left their mark, however, and not just for his storming the gates at La Scala; nearly the entire first half of what would become This Is Cinerama was supervised either by him or by Mike Jr. In the few years left to him (he died in a plane crash in March 1958), Todd would have his own story about his departure from Cinerama, a sort of you-can’t-quit-me-I’m-fired version. He said his associates at Thomas-Todd and Cinerama Inc. were too conservative and wary of taking chances: “We can’t stay on that roller-coaster and in the canals of Venice forever. Somebody has to say ‘I love you’ some day.” He also thought he could do better than Cinerama’s three-frame picture, and he wasted little time enlisting the services of the American Optical Company to develop the 70mm Todd-AO process, the only one of Cinerama’s many progeny that ever really challenged its supremacy.

But that was still in the unseeable future. Now, with Todd safely out of the way, Thomas and Cooper secured an additional $600,000 to complete their picture. To counteract the largely static footage in all those European sections, Cooper had the Cinerama camera in fairly constant motion for the two long sequences that would make up the second half. First was a colorful aquacade at Florida’s Cypress Gardens (coincidentally, much of the show consisted of athletic young men and nubile bathing beauties cavorting on Fred Waller’s other invention, water skis).

For the grand finale, Cooper hired stunt flyer Paul Mantz to pilot a modified B-25 bomber across the country for a bird’s-eye view of the natural and man-made wonders of America, set to the tune of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir singing “America the Beautiful”. Cooper also took on the task of determining what would go into the feature, and in what order — where others wanted to save the rollercoaster for the climax of the picture, Cooper insisted on hitting ’em hard right out of the gate. Preparations for the premiere proceeded feverishly right up to the last minute — Mantz’s “amber waves of grain” shots weren’t ready for the projectors until just twelve hours before showtime.

And, as we’ve seen, the result was a triumph beyond the dreams of everyone involved. New York Times critic Bosley Crowther, in an unprecedented front-page review, called it “an historic event in the history of motion pictures.” Cinerama, as it was called before This Is was added to the title, became overnight the hottest ticket on Broadway. Everyone in the picture business recognized it at once as a game-changer — much more so, in fact, than they had The Jazz Singer in 1927.

The question on everyone’s lips in the weeks that followed was the same one that Fred Waller, Lowell Thomas, Buz Reeves and their investors were asking themselves: What’s next for Cinerama?

To be continued…

Ups and Downs of the Rollercoaster, Part 3

Lowell Thomas decided right off the bat — and Merian Cooper, when he came aboard, concurred — that the star of the first Cinerama picture would be Cinerama itself. “If Charlie Chaplin had offered to do Hamlet for us,” Thomas remembered, “I’d have turned him down. I didn’t want people judging Chaplin or rediscovering Shakespeare…The advent of something as new and important as Cinerama was a major event in the history of entertainment and I was determined to let nothing upstage it.” In other words, This Is Cinerama wasn’t a movie, it was a demonstration, just like Waller and Reeves’s screenings at their tennis court command post in Oyster Bay. The difference this time was that the presentation was more organized and formal, with tuxedo-clad personnel escorting the audience to their seats — and it was in Technicolor. (Mostly, anyhow; when opening night loomed and the feature was still a little short, Thomas and Cooper decided to splice in Waller’s black-and-white clip of the Long Island Choral Society singing Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus — it made a good demo of the sound system, with an invisible choir marching down the aisles of the theater before coming into view on the screen.) So in a sense, Cinerama was exactly where it was before the opening — only now the whole world was watching.

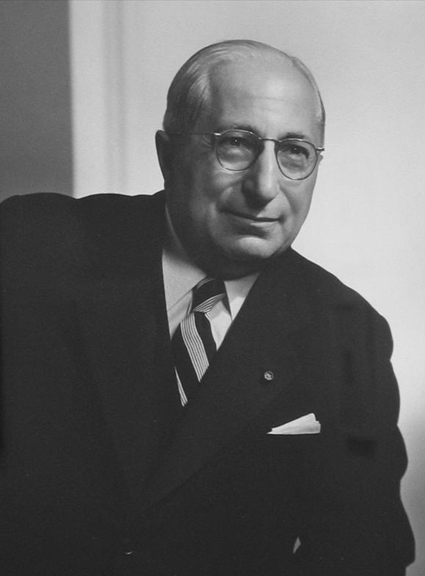

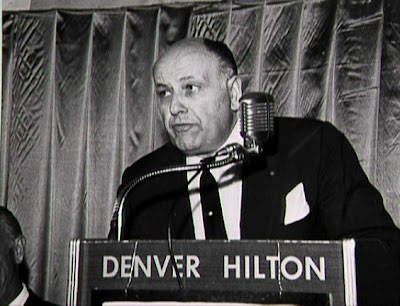

Lowell Thomas decided right off the bat — and Merian Cooper, when he came aboard, concurred — that the star of the first Cinerama picture would be Cinerama itself. “If Charlie Chaplin had offered to do Hamlet for us,” Thomas remembered, “I’d have turned him down. I didn’t want people judging Chaplin or rediscovering Shakespeare…The advent of something as new and important as Cinerama was a major event in the history of entertainment and I was determined to let nothing upstage it.” In other words, This Is Cinerama wasn’t a movie, it was a demonstration, just like Waller and Reeves’s screenings at their tennis court command post in Oyster Bay. The difference this time was that the presentation was more organized and formal, with tuxedo-clad personnel escorting the audience to their seats — and it was in Technicolor. (Mostly, anyhow; when opening night loomed and the feature was still a little short, Thomas and Cooper decided to splice in Waller’s black-and-white clip of the Long Island Choral Society singing Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus — it made a good demo of the sound system, with an invisible choir marching down the aisles of the theater before coming into view on the screen.) So in a sense, Cinerama was exactly where it was before the opening — only now the whole world was watching.  The first new development, barely three weeks after the premiere, was the appointment of Louis B. Mayer as chairman of the board of Cinerama Productions Corp. (with Lowell Thomas stepping down to vice-chairman). There was a certain irony in this; Mayer was one of the movie industry figures who trooped out to Long Island for those demonstrations, only to take a pass on investing. Back then, Mayer had been probably the most powerful man in Hollywood, but this was now. In the interim there had been that ugly power struggle at MGM between Mayer and Dore Schary, ending in a humiliating palace coup that sent Mayer packing in July 1951. By October ’52, Mayer was restless in forced retirement, and Cinerama looked like his passport back into the business. For Cinerama it was a windfall in both money (Mayer’s personal investment reportedly amounted to over $1 million) and prestige: Mayer’s status as a pioneer and longtime chief of the Tiffany of Hollywood studios gave an aura of solidity to Cinerama, and his reputation for showbiz acumen was expected to reassure and attract investors. He brought along some possible material, too: Mayer personally held the screen rights to several properties. One of them, Blossom Time, a moldy Viennese operetta of the sort Mayer had once so lovingly dusted off for Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald, would never do. But others might work very nicely, like the Lerner and Loewe musical Paint Your Wagon and the Biblical epic Joseph and His Brethren.

The first new development, barely three weeks after the premiere, was the appointment of Louis B. Mayer as chairman of the board of Cinerama Productions Corp. (with Lowell Thomas stepping down to vice-chairman). There was a certain irony in this; Mayer was one of the movie industry figures who trooped out to Long Island for those demonstrations, only to take a pass on investing. Back then, Mayer had been probably the most powerful man in Hollywood, but this was now. In the interim there had been that ugly power struggle at MGM between Mayer and Dore Schary, ending in a humiliating palace coup that sent Mayer packing in July 1951. By October ’52, Mayer was restless in forced retirement, and Cinerama looked like his passport back into the business. For Cinerama it was a windfall in both money (Mayer’s personal investment reportedly amounted to over $1 million) and prestige: Mayer’s status as a pioneer and longtime chief of the Tiffany of Hollywood studios gave an aura of solidity to Cinerama, and his reputation for showbiz acumen was expected to reassure and attract investors. He brought along some possible material, too: Mayer personally held the screen rights to several properties. One of them, Blossom Time, a moldy Viennese operetta of the sort Mayer had once so lovingly dusted off for Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald, would never do. But others might work very nicely, like the Lerner and Loewe musical Paint Your Wagon and the Biblical epic Joseph and His Brethren. There was a flurry of announcements in trade papers. Dudley Roberts, president of Cinerama Productions, said Cinerama would open theaters in 100 cities, to be supplied with six to eight full-length features a year. Merian Cooper, now head of production, promised that Cinerama would either buy or build its own studio in Hollywood. (Might Cooper have had his eye on RKO? The studio was then in the process of being run into the ground by Howard Hughes, and ripe for the picking. If so, it didn’t happen; when RKO finally sold it went first to General Tire and Rubber Co., then to Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, who renamed it Desilu.)

There was a flurry of announcements in trade papers. Dudley Roberts, president of Cinerama Productions, said Cinerama would open theaters in 100 cities, to be supplied with six to eight full-length features a year. Merian Cooper, now head of production, promised that Cinerama would either buy or build its own studio in Hollywood. (Might Cooper have had his eye on RKO? The studio was then in the process of being run into the ground by Howard Hughes, and ripe for the picking. If so, it didn’t happen; when RKO finally sold it went first to General Tire and Rubber Co., then to Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, who renamed it Desilu.) The first dramatic Cinerama picture, Cooper said, would begin shooting within two months with himself producing and directing, followed within a year by a second feature, probably directed by Cooper’s Argosy Films partner John Ford. (As it happened, Ford didn’t work in Cinerama until almost ten years later, and he wasn’t happy with it or well suited, contributing the shortest and weakest episode of How the West Was Won.)

An array of productions were considered, and some even announced. Paint Your Wagon. Tolstoy’s War and Peace. A remake of King Kong. Lawrence of Arabia (this would have been a much different picture from the one we eventually got; Lowell Thomas didn’t much care for David Lean’s 1962 take on his old friend). Paul Mantz climbed back in the cockpit of his converted B-25 and shot another 200,000 feet, at a cost of $500,000, without anybody knowing when or how it would be used.

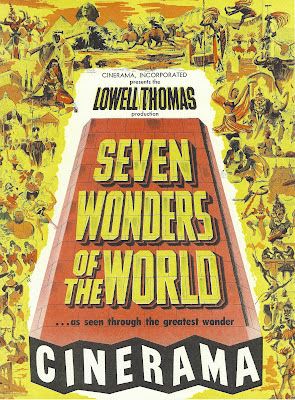

Some of Mantz’s footage eventually wound up in Seven Wonders of the World (’56). But as for all those other ambitious plans, none of them ever came to pass.

Part of the reason was L.B. Mayer himself. Biographer Scott Eyman speculates that Mayer’s enthusiasm for Cinerama was never that great in the first place; he may have been clinging to the forlorn hope that his exile from MGM was only temporary, intending Cinerama as a base from which to stage a return to Culver City. Whatever his intentions, the battle with Dore Schary had left him, in Lowell Thomas’s words, “aging, tired [and] unable to make up his mind about anything.” (Eyman memorably quotes writer Gavin Lambert, who covered Mayer at the time, in almost the same words: “He was an aging, tired man in a dark suit, who looked like a businessman but was actually an exiled emperor.”) Mayer eventually left Cinerama, though sources vary on exactly when. Eyman dates Mayer’s departure to November 1954; Thomas Erffmeyer’s history implies (and an article in the Winter 1992 issue of The Perfect Vision says outright) that it may have been as early as May ’53. In any event, Cinerama Productions Corp. produced nothing under Mayer’s chairmanship, and frittered away much of its early momentum.

Ups and Downs of the Rollercoaster, Part 4

Remember all those movie-industry honchos trekking out to Oyster Bay to see Cinerama? One of them was Joseph M. Schenck, chairman of the board of 20th Century Fox. Like everybody else, Schenck passed on Cinerama, but as he did so he added ruefully: “I’ll be buying this process someday, and it will cost me ten times as much.”

Remember all those movie-industry honchos trekking out to Oyster Bay to see Cinerama? One of them was Joseph M. Schenck, chairman of the board of 20th Century Fox. Like everybody else, Schenck passed on Cinerama, but as he did so he added ruefully: “I’ll be buying this process someday, and it will cost me ten times as much.” Early ads for CinemaScope, like the one I’ve reproduced here, emphasized a resemblance to both Cinerama and 3-D (“It’s the miracle you see without glasses!”) that didn’t really exist. While CinemaScope did originally call for a curved screen, most theaters didn’t bother with that. Even in The Robe‘s first-run engagements, the curve was much shallower than in this ad, and nowhere near as deep as Cinerama’s. (A good thing, too: you have to feel sorry for that poor sucker on the left end of the seventh row — what kind of view could he have had?) Anybody who compared Cinerama and CinemaScope side-by-side (so to speak) could see there was no real comparison. But in truth, most moviegoers couldn’t do that. Among Hollywood professionals, CinemaScope didn’t have to be as good as Cinerama, as long as they could sell it that way to the millions who hadn’t yet seen the real McCoy. Besides, it was still a huge change from movies-as-usual, and something folks couldn’t get on those newfangled 17-inch black and white TV screens in their living rooms.

Early ads for CinemaScope, like the one I’ve reproduced here, emphasized a resemblance to both Cinerama and 3-D (“It’s the miracle you see without glasses!”) that didn’t really exist. While CinemaScope did originally call for a curved screen, most theaters didn’t bother with that. Even in The Robe‘s first-run engagements, the curve was much shallower than in this ad, and nowhere near as deep as Cinerama’s. (A good thing, too: you have to feel sorry for that poor sucker on the left end of the seventh row — what kind of view could he have had?) Anybody who compared Cinerama and CinemaScope side-by-side (so to speak) could see there was no real comparison. But in truth, most moviegoers couldn’t do that. Among Hollywood professionals, CinemaScope didn’t have to be as good as Cinerama, as long as they could sell it that way to the millions who hadn’t yet seen the real McCoy. Besides, it was still a huge change from movies-as-usual, and something folks couldn’t get on those newfangled 17-inch black and white TV screens in their living rooms.

And it was relatively cheap. While the Cinerama people did their best to lowball the estimated cost of converting a theater, the truth was it could run as high as $200,000. Moreover, hundreds of seats could be lost either to make room for the three projection booths or because of unacceptable viewing angles, thus limiting potential revenue. Conversely, CinemaScope (Fox promised) could be installed with no loss of seats, and for the mere cost of a set of lenses, a new screen, and a three-channel magnetic sound system — a sizeable investment, yes, but nothing like the fortune needed for Cinerama. (This is a good time to remind you that we’re talking about Eisenhower dollars here; to get a sense of 2022 equivalents, you should multiply by about 11.25 — $2,250,000.)

Fox mounted an aggressive and well-organized campaign to promote CinemaScope (Skouras was battling a hostile takeover, so ‘Scope had to succeed), and in the end it would effectively sink Cinerama Productions Corp.’s hopes of partnering with one of the major studios. Even as early as March and April ’53, when Fox began holding nationwide demonstrations of CinemaScope for industry and press, Cinerama was feeling the pinch. Not only were leads on new investment drying up, but some contractually committed investors were backing out, citing a “changed circumstances” escape clause in their contracts. Cinerama still had only three venues in the world (a fourth, the Palace in Chicago, wouldn’t open until July due to a protracted haggle with the local projectionists’ union). Cinerama Productions Corp. had to find funding to supplement their high-overhead box-office take if they were going to open more theaters and maintain a foothold in the market they had created, to say nothing of producing follow-up features to This Is Cinerama.

They considered their options. A public stock offering was one, but sales of Cinerama Inc. stock had already been less than expected. Another possibility was to seek financial participation from a theater circuit rather than a studio, and they decided on that. A logical choice for such an arrangement was the Stanley Warner Corporation, since Cinerama had already been dealing with them: the newly Cineramified Warner Theatre in Los Angeles was theirs, and This Is Cinerama was slated to move from the Broadway Theatre to New York’s Warner in June 1953 (the Shubert brothers wanted their house back).

Before we go on, a clarification: “Stanley Warner” wasn’t a person. How the name came about (as simple as I can make it) was this: Stanley Warner’s president was S.H. Fabian, who had gotten into the theater business in his father’s small circuit of houses in New Jersey in the 1920s. In 1926 Fabian Theatres merged with another chain, Stanley Company of America. Two years later that circuit was acquired by Warner Bros. for the exhibition of their pictures, and Fabian partnered with one Samuel Rosen to rebuild his own chain in New York State, Fabian Enterprises. In the early 1950s, when federal antitrust action compelled the studios to divest themselves of their theater chains, Fabian went to Harry, Albert and Jack Warner to (essentially) buy his old theaters back. The corporation he formed for this might have been called Fabian Rosen, or Warner Fabian, but instead it was Stanley Warner.

Before we go on, a clarification: “Stanley Warner” wasn’t a person. How the name came about (as simple as I can make it) was this: Stanley Warner’s president was S.H. Fabian, who had gotten into the theater business in his father’s small circuit of houses in New Jersey in the 1920s. In 1926 Fabian Theatres merged with another chain, Stanley Company of America. Two years later that circuit was acquired by Warner Bros. for the exhibition of their pictures, and Fabian partnered with one Samuel Rosen to rebuild his own chain in New York State, Fabian Enterprises. In the early 1950s, when federal antitrust action compelled the studios to divest themselves of their theater chains, Fabian went to Harry, Albert and Jack Warner to (essentially) buy his old theaters back. The corporation he formed for this might have been called Fabian Rosen, or Warner Fabian, but instead it was Stanley Warner.As the corporate heir (as it were) to Warner Bros. Theatres, Stanley Warner became a party to the federal suit’s consent decree, and needed approval from federal court (and by extension the U.S. Dept. of Justice) for any venture into movie production, distribution or exhibition. That included any agreement with Cinerama Productions Corp., so it added yet another layer of negotiation. A tentative agreement for Stanley Warner to take over Cinerama theater operations was announced in May 1953, but there were a multitude of details to work out. Cinerama Productions’ licensing agreement with Cinerama Inc. ran only through 1956, so Stanley Warner wanted a two-year extension of that to help recoup their investment. They also wanted control of production and distribution as well as exhibition, to ensure a steady flow of pictures for the theaters. Meanwhile, Cinerama Productions was behind in payments to Cinerama Inc. for equipment, so Cinerama Inc. wanted at least something towards that before any talk about extending the license. And the Dept. of Justice had their own demands before they’d recommend court approval.

It took three months of intense dickering to sort this all out, with the clock ticking — if court approval wasn’t received by August 15, the whole deal was off. They finally made it with four days to spare, and the deal was this: For a little over $2.5 million, Stanley Warner essentially bought control of Cinerama Productions Corp. through 1958, adding yet another layer to the corporate tangle with its wholly-owned subsidiary Stanley Warner Cinerama. They would produce at least five Cinerama pictures but (the feds insisted) no more than 15. For each feature they could also produce a conventional 35mm version, but (again, per the feds) could not exhibit the 35mm versions in any of the Cinerama theaters. And — yet again, here was the hand of the U.S. Dept. of Justice — Stanley Warner could open no more than 24 Cinerama theaters in the United States. (So much for Dudley Roberts’s dream of a hundred theaters getting six to eight pictures a year.)

A month later, on September 16, 1953, The Robe premiered to respectful reviews and boffo box office. 20th Century Fox had three more CinemaScope pictures ready to go, MGM had one, and dozens more were in various states of production at one studio or another. Spyros Skouras’s gamble had paid off in a big way.

Ups and Downs of the Rollercoaster, Part 5

In his 1977 memoir So Long Until Tomorrow, the 85-year-old Lowell Thomas — with nearly a quarter-century of frustrated hindsight — remembered the Stanley Warner deal thus:

In his 1977 memoir So Long Until Tomorrow, the 85-year-old Lowell Thomas — with nearly a quarter-century of frustrated hindsight — remembered the Stanley Warner deal thus:“Our original group of founders had dwindled — Fred Waller, the gentle, bespectacled genius who started it all, had died before he even knew of his triumph; Mike Todd was busily hustling and working with American Optical on the process to be called Todd A-O … Arrayed against [Frank Smith], Merian Cooper and me were men of wealth who had gone into Cinerama solely for the investment possibilities, and at this critical juncture, either unwilling to go looking for the additional cash or simply ready to take their already large profits, they opted to sell out.

“The buyer was the Stanley-Warner company, and from a purely practical viewpoint, maybe the decision was not all wrong. In making it we all made a lot of money. But the bells began tolling for Cinerama then and there. Stanley-Warner was a brassiere manufacturing corporation, plus owners of a major theater chain. But they were not film producers … They didn’t really know what Cinerama was all about.”

Thomas’s memory wasn’t flawless. “Stanley Warner” wasn’t hyphenated, and “Todd-AO” was. Fred Waller lived long enough to know his triumph and collect an Oscar for it; he died in May 1954, nine months after the Stanley Warner deal was approved by the court. And Stanley Warner wasn’t “a brassiere manufacturing company”. Not yet. They didn’t purchase the International Latex Corporation (maker of, among other things, the Playtex Living Bra) until April 1954, a year after buying their six-year control of Cinerama Productions Corp. (This expansion from theater operation to ladies’ undies and baby pants was an early example of the kind of diversification that ultimately led to the entertainment conglomerates of today.)

But Thomas’s basic point was well taken. The folks at Stanley Warner, it’s true, were not film producers. And despite S.H. Fabian’s advocacy of alternate entertainment technologies — he was an early proponent of drive-in theaters, 3-D, and closed-circuit theatrical television — he really didn’t know what Cinerama was all about. Even if nobody heard it at the time, the bells were definitely tolling.

Thomas can be forgiven a certain amount of bitterness. By May 1954, Stanley Warner had managed to open only seven new Cinerama theaters and had yet to complete a follow-up feature to This Is Cinerama; yet they had managed to scrape up $15 million ($166.18 million in 2022) to buy International Latex. Moreover, in the next four years SW would lavish far more care and resources on International Latex, where profit margins were high and they were not under the thumb of the U.S. Justice Dept. Small wonder that, decades later, Thomas remembered SW being already in the brassiere business when Cinerama came along.

Stanley Warner was contractually obligated to produce a picture within the first year, and their original plan was the same as Cinerama’s before them: to involve one of the major studios in making Cinerama pictures. In early August, even before the court approved the buyout, talks were held with Columbia, Paramount and Warner Bros. All came to nothing, including a proposed picture about the Lewis and Clark expedition to star Gregory Peck and Clark Gable as the great explorers (excellent casting, that).

With the success of The Robe, studios began stampeding to CinemaScope in preference to the more expensive Cinerama, and any chance of a deal in that direction evaporated. SW negotiated with Merian Cooper, who was thinking of molding Paul Mantz’s 200,000 feet of aerial footage into a picture to be called Seven Wonders of the World, but talks broke down when they couldn’t agree on a completion schedule.

Cinerama Inc. made most of its money from the equipping of Cinerama theaters — the sale or lease of equipment and supplying of replacement parts — and was annoyed that Stanley Warner wasn’t opening theaters at a quicker pace. The remaining investors in Cinerama Productions were annoyed that SW wasn’t opening more theaters and producing a steadier stream of pictures to show in them. And Stanley Warner, who had to put up all the money for both the theaters and the pictures but had to share almost half of any profits (when operating costs alone could eat up as much as 90 percent of gross ticket sales), was beginning to wonder if investing in the process had been such a good idea in the first place. The cracks among the partners in Cinerama were beginning to show, and were the subject of chatter in the trade press.

Cinerama Inc. made most of its money from the equipping of Cinerama theaters — the sale or lease of equipment and supplying of replacement parts — and was annoyed that Stanley Warner wasn’t opening theaters at a quicker pace. The remaining investors in Cinerama Productions were annoyed that SW wasn’t opening more theaters and producing a steadier stream of pictures to show in them. And Stanley Warner, who had to put up all the money for both the theaters and the pictures but had to share almost half of any profits (when operating costs alone could eat up as much as 90 percent of gross ticket sales), was beginning to wonder if investing in the process had been such a good idea in the first place. The cracks among the partners in Cinerama were beginning to show, and were the subject of chatter in the trade press. There had been talk of plans to expand Cinerama into foreign countries almost from the first opening in September 1952, but nothing had ever come of that idea. In the spring of 1954, Stanley Warner sought to farm out the foreign exhibition rights — find somebody who would foot the bill for overseas expansion and pay SW for the privilege. After three months of negotiations, S.H. Fabian hammered out a deal with Nicolas Reisini, president of Robin International.

There had been talk of plans to expand Cinerama into foreign countries almost from the first opening in September 1952, but nothing had ever come of that idea. In the spring of 1954, Stanley Warner sought to farm out the foreign exhibition rights — find somebody who would foot the bill for overseas expansion and pay SW for the privilege. After three months of negotiations, S.H. Fabian hammered out a deal with Nicolas Reisini, president of Robin International.Neither Robin International nor the Greek-born Reisini had any experience in the movie business. Robin International was reportedly an import/export company, although exactly what it imported and exported wasn’t clear. Nothing shady, mind you, it’s just that Reisini seems to have had his fingers in a bewildering number of pies — none of them having anything to do with the movie industry.

But there was another factor. According to his son Andrew (interviewed for David Strohmaier’s 2002 documentary Cinerama Adventure), Nicolas Reisini as a young man had seen the Paris premiere of Abel Gance’s Napoleon in 1927 and been spellbound — especially by Gance’s three-screen “Polyvision” triptych that climaxed the picture. When Reisini saw This Is Cinerama in New York in late ’52 or early ’53, it revived that youthful excitement and seemed to be the fulfillment of Gance’s earlier vision. Son Andrew says Reisini decided on the spot that he wanted to get in on Cinerama one way or another, and when Stanley Warner went looking for someone to buy foreign rights, Reisini was ready.

Meanwhile, back home, Stanley Warner and Louis de Rochemont had fallen out over money — and SW’s reluctance to invest in perfecting the Cinerama process. De Rochemont stalked off to produce Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich in CineMiracle (a competing process just different enough to avoid infringing Cinerama’s patents). SW had enticed Lowell Thomas back to produce Seven Wonders of the World (revived after the departure of Merian Cooper). Shooting wrapped in June ’55, but as with This Is Cinerama before it, Cinerama Holiday was drawing so strongly that SW was in no hurry to release Seven Wonders (it finally opened in April 1956).

Meanwhile, back home, Stanley Warner and Louis de Rochemont had fallen out over money — and SW’s reluctance to invest in perfecting the Cinerama process. De Rochemont stalked off to produce Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich in CineMiracle (a competing process just different enough to avoid infringing Cinerama’s patents). SW had enticed Lowell Thomas back to produce Seven Wonders of the World (revived after the departure of Merian Cooper). Shooting wrapped in June ’55, but as with This Is Cinerama before it, Cinerama Holiday was drawing so strongly that SW was in no hurry to release Seven Wonders (it finally opened in April 1956).To be concluded…

Ups and Downs of the Rollercoaster, Part 6

There’s just no getting around the fact that Stanley Warner’s management of Cinerama was a disaster from the word go. To be fair, the limits imposed by the court gave SW little incentive to think beyond the short term: They could have no more than 24 Cinerama theaters, and they had to be out of Cinerama by the end of 1958 (SW did get a court-approved extension to that deadline). Still, with the purchase of International Latex, Stanley Warner behaved like a kid with a new toy. Cinerama became the old toy.

There’s just no getting around the fact that Stanley Warner’s management of Cinerama was a disaster from the word go. To be fair, the limits imposed by the court gave SW little incentive to think beyond the short term: They could have no more than 24 Cinerama theaters, and they had to be out of Cinerama by the end of 1958 (SW did get a court-approved extension to that deadline). Still, with the purchase of International Latex, Stanley Warner behaved like a kid with a new toy. Cinerama became the old toy.SW never operated more than 22 Cinerama theaters at one time, and they never produced enough pictures to keep even those busy (and nowhere near the court-imposed limit of 15 pictures). When they did produce a new Cinerama picture, all they could think to do was produce yet another travelogue, the only real change being where the picture traveled to. Even then, as we have seen, SW would delay release until they had wrung the current release dry; they insisted every picture had to premiere in New York, yet they wouldn’t open a second New York theater. Nor would they even consider beginning a new picture while they had one waiting in the wings; the idea of creating a backlog of pictures ready to go appears never to have been considered.

In 1957, when the foreign-rights agreement with Robin International expired, Stanley Warner ventured into that area themselves. They learned a lesson, though, from Nicolas Reisini’s practice of sub-licensing Cinerama to local exhibitors, who would pay to convert a theater, then lease rather than purchase the equipment from Cinerama Inc. Essentially, what Reisini had done, and what SW did now, was to sell Cinerama “franchises”. It was a policy that might have served Cinerama well from the outset — and indeed Reisini would employ it with some success after he took the driver’s seat — but it seems not to have occurred to anyone before Reisini came along.

Part of the problem all along was Cinerama’s Byzantine corporate structure, which hampered any attempt to strategize Cinerama for the long run. Instead of one central corporation, Cinerama was first three, then four, all severely under-capitalized and with complicated financial relations. A serious simplification of the arrangement was called for, but Stanley Warner never made any effort in that direction.

Reeves’s proven management skills might have turned Cinerama around even then if he had taken the reins in a firm hand, but evidently that was never his intention. With hindsight, it appears that Reeves was simply tired of dealing with Cinerama; his concerted efforts to streamline Cinerama’s corporate structure may have been just a way of getting it in good order — like a real-estate speculator fixing up and flipping a rundown house — so he could sell it and roll the capital into his own company, Reeves Soundcraft. In any event, Reeves had control of Cinerama for less than a year before he put it on the market — negotiating first with Walter Reade Jr. of Reade Theatres, then with Nicolas Reisini of Robin International. In the end Reisini bought Reeves out, becoming president and CEO of Cinerama Inc. (In his history of Cinerama, Thomas Erffmeyer mentions that in 1947 Reisini had purchased a California asbestos mine for $350,000 — which now, in 1959, he sold for $4 million. Dr. Erffmeyer doesn’t say if it was this windfall which enabled Reisini to buy Cinerama Inc., but it strikes me as a logical inference.)

Reeves’s proven management skills might have turned Cinerama around even then if he had taken the reins in a firm hand, but evidently that was never his intention. With hindsight, it appears that Reeves was simply tired of dealing with Cinerama; his concerted efforts to streamline Cinerama’s corporate structure may have been just a way of getting it in good order — like a real-estate speculator fixing up and flipping a rundown house — so he could sell it and roll the capital into his own company, Reeves Soundcraft. In any event, Reeves had control of Cinerama for less than a year before he put it on the market — negotiating first with Walter Reade Jr. of Reade Theatres, then with Nicolas Reisini of Robin International. In the end Reisini bought Reeves out, becoming president and CEO of Cinerama Inc. (In his history of Cinerama, Thomas Erffmeyer mentions that in 1947 Reisini had purchased a California asbestos mine for $350,000 — which now, in 1959, he sold for $4 million. Dr. Erffmeyer doesn’t say if it was this windfall which enabled Reisini to buy Cinerama Inc., but it strikes me as a logical inference.)Nicolas Reisini was, if nothing else, an energetic and ambitious entrepreneur and wheeler-dealer, and he hit the ground running. Even before assuming the presidency of Cinerama in May 1960, he accomplished something nobody before him had been able to do: He established a co-production agreement with a major studio. The studio was MGM (then flush with the critical and box-office success of Ben-Hur), and the agreement was announced on December 11, 1959: They would produce at least two and as many as six features; MGM production chief Sol C. Siegel would supervise them, with Cinerama having script, director and cast approval; Cinerama would distribute and exhibit the pictures in their theaters, and MGM would handle distribution of 35mm general release versions after the Cinerama roadshow engagements.

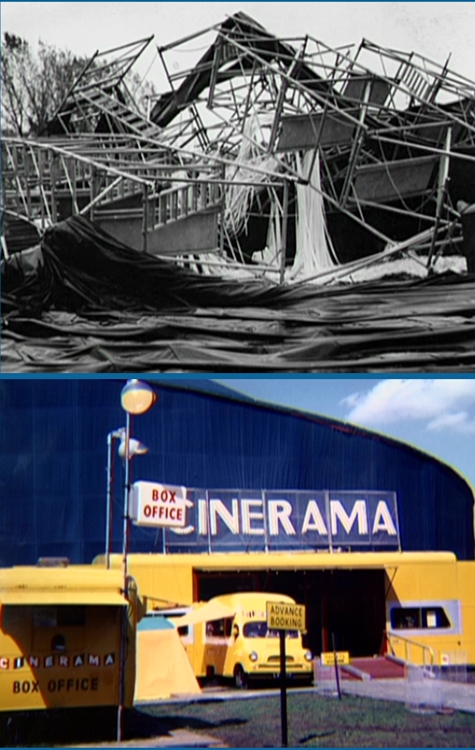

A top priority for Reisini was to bring Cinerama to the widest possible audience — to increase its fan base, if you will. To that end he followed through on an idea Stanley Warner had flirted with in the mid-’50s but (typically) abandoned before doing much with it: portable Cinerama. A caravan of trucks criss-crossed France and other countries in Europe, visiting towns and villages like a 19th century travelling circus. The caravan would set up an enormous inflatable rubber tent — inflatable so it would be self-supporting with no internal columns or poles to block the view of the screen — that could seat up to 3,000 spectators on folding chairs. (Reisini had always been adept at thinking outside the box. In 1954, when Robin International undertook to open theaters overseas, he had tried to interest the United States Information Agency in mounting a travelling Cinerama theater on a retired aircraft carrier. USIA was game, and even President Eisenhower liked the idea, but Congress nipped it in the bud.)

A top priority for Reisini was to bring Cinerama to the widest possible audience — to increase its fan base, if you will. To that end he followed through on an idea Stanley Warner had flirted with in the mid-’50s but (typically) abandoned before doing much with it: portable Cinerama. A caravan of trucks criss-crossed France and other countries in Europe, visiting towns and villages like a 19th century travelling circus. The caravan would set up an enormous inflatable rubber tent — inflatable so it would be self-supporting with no internal columns or poles to block the view of the screen — that could seat up to 3,000 spectators on folding chairs. (Reisini had always been adept at thinking outside the box. In 1954, when Robin International undertook to open theaters overseas, he had tried to interest the United States Information Agency in mounting a travelling Cinerama theater on a retired aircraft carrier. USIA was game, and even President Eisenhower liked the idea, but Congress nipped it in the bud.)

It wasn’t enough to save his job. Enter William Forman of Pacific Theatres. Several of his theaters had installed Cinerama equipment, and Forman jumped in with both feet in February ’63: for $15 million he bought up the note Prudential Insurance Co. held from their 1959 loan of $12 million, and with it he acquired a series of stock options, all of which he excercised, to the point where he replaced Nicolas Reisini as president and CEO in December ’63. Reisini remained as chairman of the board for the time being, but in September ’64, with Cinerama Inc. teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, he resigned even from that, effective immediately.

Next time: The technology of Cinerama…

Nuts and Bolts of the Rollercoaster

At This Is Cinerama‘s premiere on September 30, 1952, historian Greg Kimble tells us, Lowell Thomas and Merian Cooper were as nervous as expectant fathers. But not Fred Waller; he sat quietly confident, and as the cheers and bravos echoed at the end, he allowed himself only the slightest of smiles. “I knew 16 years ago,” he said, “it would be like this.”

Even so, Waller never considered that night’s showing to be Cinerama in its final form; this was, in a sense, only the “third generation” version. Just as he had refined Vitarama’s 11 cameras and projectors down to five, and those five down to Cinerama’s three, he fully expected that the process would continue to evolve, and that he would be there to see it was done.

Truth be told, there was room for improvement, and Waller knew it.

Some of Cinerama’s technical problems can be discerned in this frame (frames, actually) from Search for Paradise — although to be fair, by the time this picture was shot most of them had been considerably alleviated. Most often complained about were those dividing lines between the three panels. The panels overlapped by a degree or two, which meant that the overlap area would inevitably get the light from two projectors. To minimize this over-exposure, the sides of each projector’s film gate were supplied with little devices called (spellings vary) “gigolos”. These were serrated, comb-like assemblies mounted on cams that moved them up and down, once for each frame (i.e., 26 times per second) as the film passed through the gate. This was intended to cut down on the excess light hitting the overlap, and to blur the sharp division from one panel to the next. As a matter of fact, this worked reasonably well.

Some of Cinerama’s technical problems can be discerned in this frame (frames, actually) from Search for Paradise — although to be fair, by the time this picture was shot most of them had been considerably alleviated. Most often complained about were those dividing lines between the three panels. The panels overlapped by a degree or two, which meant that the overlap area would inevitably get the light from two projectors. To minimize this over-exposure, the sides of each projector’s film gate were supplied with little devices called (spellings vary) “gigolos”. These were serrated, comb-like assemblies mounted on cams that moved them up and down, once for each frame (i.e., 26 times per second) as the film passed through the gate. This was intended to cut down on the excess light hitting the overlap, and to blur the sharp division from one panel to the next. As a matter of fact, this worked reasonably well. Most noticeable of all was the parallax effect caused by the fact that the Cinerama camera was really three cameras, each with its own vanishing point. (“parallax [pár-a-laks] n. 1 the apparent difference in the position or direction of an object caused when the observer’s position is changed.”) Imagine yourself looking out at a vista: First you look straight ahead; then you take a step to your right and turn your head left; then two steps left and turn your head right. You’re looking at the same view each time, but from three ever-so-slightly different places. That’s parallax. Take this frame on the right, from the last scene of How the West Was Won, flying under the Golden Gate Bridge. The join lines and the difference in color textures from one panel to the next are glaringly obvious, but even more pronounced are the “elbows” in the bridge; everyone knows that the Golden Gate travels in a perfectly straght line between San Francisco on the left and Marin County on the right.

Most noticeable of all was the parallax effect caused by the fact that the Cinerama camera was really three cameras, each with its own vanishing point. (“parallax [pár-a-laks] n. 1 the apparent difference in the position or direction of an object caused when the observer’s position is changed.”) Imagine yourself looking out at a vista: First you look straight ahead; then you take a step to your right and turn your head left; then two steps left and turn your head right. You’re looking at the same view each time, but from three ever-so-slightly different places. That’s parallax. Take this frame on the right, from the last scene of How the West Was Won, flying under the Golden Gate Bridge. The join lines and the difference in color textures from one panel to the next are glaringly obvious, but even more pronounced are the “elbows” in the bridge; everyone knows that the Golden Gate travels in a perfectly straght line between San Francisco on the left and Marin County on the right.

Here’s a similar frame, on the left, from the same scene as it appears in a later DVD issue. The digital clean-up crew has been busy: Join lines have been digitally erased, the color has been made uniform, and the “elbows” have been smoothed out. But the digital wizards couldn’t do anything about how the three lenses saw the bridge. That’s how it was with the Cinerama camera. The parallax wasn’t always obvious — especially when you were careening up and down rollercoaster tracks or swooping over Niagara Falls or through Zion Canyon in Utah — but when it was, it was impossible to ignore.

As for the problem of slight variations in color, that was dependent on printing standards, which in most laboratories, as Hazard Reeves admitted, “have never been tight. If necessary,” he went on, “we’ll do our own printing.” But once again he ran up against the cheapskates at Stanley Warner. Not until 1958 did they agree to allot $200,000 for research into improved printing standards, and it wasn’t enough; Cinerama’s special in-house printers never materialized.

The Man Who Saved Cinerama

Let us now praise John Harvey.

Let us now praise John Harvey.

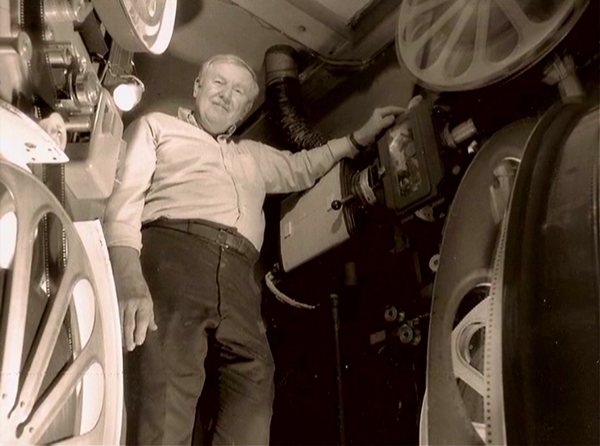

Harvey’s interest in the movie projectionist’s craft began at an early age in Dayton. At the age of 10 he’d tag along when his older brother went to work at the local drive-in theater, and he began to wonder about the kind of machine it would take to project movies onto that massive outdoor screen. The projectionist noticed him peering in the windows night after night, invited him in to have a look around, and became his mentor, eventually sponsoring him into the projectionists’ union when John turned 17.

Harvey’s interest in the movie projectionist’s craft began at an early age in Dayton. At the age of 10 he’d tag along when his older brother went to work at the local drive-in theater, and he began to wonder about the kind of machine it would take to project movies onto that massive outdoor screen. The projectionist noticed him peering in the windows night after night, invited him in to have a look around, and became his mentor, eventually sponsoring him into the projectionists’ union when John turned 17. When three-strip Cinerama was abandoned after HTWWW, Harvey missed it. He saw clearly the difference with the “new” Cinerama movies like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World and The Greatest Story Ever Told (really only UltraPanavision — a big picture on a curved screen, but the viewer was no more “in” the picture than if he were standing in front of a billboard by the side of the road).

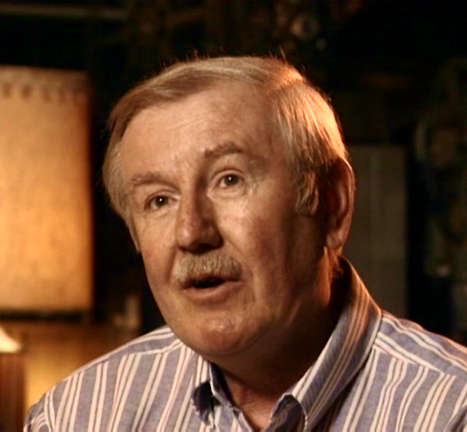

When three-strip Cinerama was abandoned after HTWWW, Harvey missed it. He saw clearly the difference with the “new” Cinerama movies like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World and The Greatest Story Ever Told (really only UltraPanavision — a big picture on a curved screen, but the viewer was no more “in” the picture than if he were standing in front of a billboard by the side of the road). In the early 1980s a mutual friend invited Larry Smith to a screening at John’s home and introduced the two men. Smith remembered seeing Cinerama at the Dabel at the age of six, and his experience that night was a reunion with one of his most vivid childhood memories. He told Harvey that if there was any way he (Larry) could help bring this to a wider audience, he wanted to do it. In 1986, Smith became the manager of the New Neon Movies, a cozy little 300-seat art cinema nestled in one corner of a huge parking garage in downtown Dayton, and began a ten-year campaign to persuade Harvey to install his Cinerama equipment at the New Neon. (This picture, by the way, is a rather misleading likeness of Larry. It’s from a 1997 interview taken while Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet was playing at the New Neon, and Larry had bleached his hair and grown the moustache and soul-patch to emphasize his slight resemblance to Branagh as the Melancholy Dane.)

In the early 1980s a mutual friend invited Larry Smith to a screening at John’s home and introduced the two men. Smith remembered seeing Cinerama at the Dabel at the age of six, and his experience that night was a reunion with one of his most vivid childhood memories. He told Harvey that if there was any way he (Larry) could help bring this to a wider audience, he wanted to do it. In 1986, Smith became the manager of the New Neon Movies, a cozy little 300-seat art cinema nestled in one corner of a huge parking garage in downtown Dayton, and began a ten-year campaign to persuade Harvey to install his Cinerama equipment at the New Neon. (This picture, by the way, is a rather misleading likeness of Larry. It’s from a 1997 interview taken while Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet was playing at the New Neon, and Larry had bleached his hair and grown the moustache and soul-patch to emphasize his slight resemblance to Branagh as the Melancholy Dane.) In John’s search for film and equipment, he had made the acquaintance of Willem Bouwmeester of the Netherlands. Like Harvey, Bouwmeester discovered Cinerama as a teenager and never lost his enthusiasm for the process. He grew up to work for IMAX in Europe and become a founding member of the International Cinerama Society, and from the Continent he had helped Harvey in his search. In 1993, when the ICS installed Cinerama at the Bradford museum, they sought and received advice and assistance from John Harvey. So now John’s house was no longer the lone outpost in a Cinerama-bereft world. But the only true Cinerama theater was in England; Cinerama remained a prophet without honor in the country of its origin (where it had once proved to be an honor without profit).

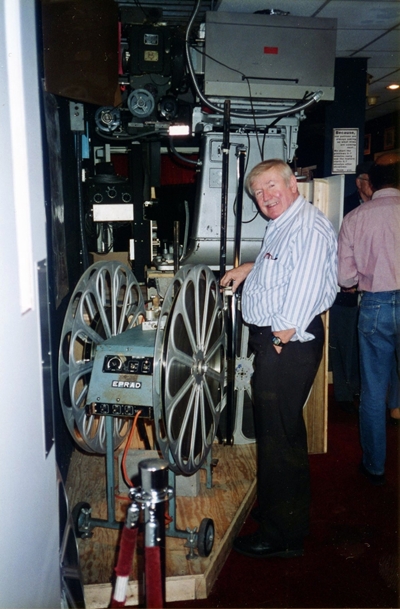

In John’s search for film and equipment, he had made the acquaintance of Willem Bouwmeester of the Netherlands. Like Harvey, Bouwmeester discovered Cinerama as a teenager and never lost his enthusiasm for the process. He grew up to work for IMAX in Europe and become a founding member of the International Cinerama Society, and from the Continent he had helped Harvey in his search. In 1993, when the ICS installed Cinerama at the Bradford museum, they sought and received advice and assistance from John Harvey. So now John’s house was no longer the lone outpost in a Cinerama-bereft world. But the only true Cinerama theater was in England; Cinerama remained a prophet without honor in the country of its origin (where it had once proved to be an honor without profit). As 1995 became 1996, the landlord of the New Neon Movies announced plans to split the already-modest theater down the middle and turn it into a two-screen venue. Larry Smith at last persuaded John it was now or never, and they hatched a plan that was brilliant simplicity itself: Before the remodel, the New Neon would install John Harvey’s screen, projectors and sound equipment. The theater would continue showing its standard art-house fare every evening, but on weekends there would be full-Cinerama matinees of This Is Cinerama (on Saturdays) and How the West Was Won (Sundays). The landlord was doubtful the scheme would pay for itself, but he agreed to let Smith solicit a letter-writing campaign; if he could get 1,000 writers to pledge to come to Dayton for Cinerama, then they could talk.

As 1995 became 1996, the landlord of the New Neon Movies announced plans to split the already-modest theater down the middle and turn it into a two-screen venue. Larry Smith at last persuaded John it was now or never, and they hatched a plan that was brilliant simplicity itself: Before the remodel, the New Neon would install John Harvey’s screen, projectors and sound equipment. The theater would continue showing its standard art-house fare every evening, but on weekends there would be full-Cinerama matinees of This Is Cinerama (on Saturdays) and How the West Was Won (Sundays). The landlord was doubtful the scheme would pay for itself, but he agreed to let Smith solicit a letter-writing campaign; if he could get 1,000 writers to pledge to come to Dayton for Cinerama, then they could talk.

I’ll never forget how I learned about the project. That summer of ’96, when my girlfriend LuAnn and I returned from vacation in Illinois and Indiana, we were picked up at the Sacramento airport by my uncle, himself on vacation from his home in Muncie, Indiana — the same uncle who had taken my parents and grandparents to see This Is Cinerama in San Francisco in 1953. As I sat down in the car, he dropped an issue of Classic Images in my lap, open to an ad announcing the eight-week return of This Is Cinerama and How the West Was Won. I stared, gobsmacked, for a few seconds, and once I realized it wasn’t some kind of trick, I turned to my uncle and said, “Let’s go.”

I’ll never forget how I learned about the project. That summer of ’96, when my girlfriend LuAnn and I returned from vacation in Illinois and Indiana, we were picked up at the Sacramento airport by my uncle, himself on vacation from his home in Muncie, Indiana — the same uncle who had taken my parents and grandparents to see This Is Cinerama in San Francisco in 1953. As I sat down in the car, he dropped an issue of Classic Images in my lap, open to an ad announcing the eight-week return of This Is Cinerama and How the West Was Won. I stared, gobsmacked, for a few seconds, and once I realized it wasn’t some kind of trick, I turned to my uncle and said, “Let’s go.”