Crazy and Crazier, Part 1

This post has grown in the planning, to the point where I’m putting it up in two parts (maybe more; we’ll see how things shake out). I have an epic tale to tell, nothing less than the rise and fall of the Hollywood musical, as reflected in the screen career of a single property: Girl Crazy, the 1930 Broadway hit with songs by George and Ira Gershwin, book by Guy Bolton and John McGowan.

This post has grown in the planning, to the point where I’m putting it up in two parts (maybe more; we’ll see how things shake out). I have an epic tale to tell, nothing less than the rise and fall of the Hollywood musical, as reflected in the screen career of a single property: Girl Crazy, the 1930 Broadway hit with songs by George and Ira Gershwin, book by Guy Bolton and John McGowan. Merman’s debut alone was enough to make Girl Crazy‘s opening a Broadway landmark, but there was more. Others present that night wouldn’t make it big until later, but the fact that they were there at all is enough to make you pray for time travel. For starters, there was the man who put together the pit orchestra: Ernest Loring “Red” Nichols, age 25, one of the busiest musicians in town. He was an accomplished cornetist who could play equally well “hot” and “straight”, and he had already made hundreds of Dixieland recordings for Brunswick Records, usually with an ad hoc band billed as Red Nichols and his Five Pennies.

Merman’s debut alone was enough to make Girl Crazy‘s opening a Broadway landmark, but there was more. Others present that night wouldn’t make it big until later, but the fact that they were there at all is enough to make you pray for time travel. For starters, there was the man who put together the pit orchestra: Ernest Loring “Red” Nichols, age 25, one of the busiest musicians in town. He was an accomplished cornetist who could play equally well “hot” and “straight”, and he had already made hundreds of Dixieland recordings for Brunswick Records, usually with an ad hoc band billed as Red Nichols and his Five Pennies. Playing Girl Crazy‘s lead was 19-year-old Ginger Rogers, fresh from making her Broadway debut in Top Speed and creating a sensation purring “Cigarette me, big boy” in her first movie, Young Man of Manhattan. She had two of Girl Crazy‘s most enduring songs, “Embraceable You” and “But Not for Me”, and by all accounts handled them quite nicely. But lacking what Cole Porter later called Ethel Merman’s “golden foghorn” voice, she had to stand helplessly by while Ethel stole her thunder night after night; it would take the intimacy of the movie camera to coax her star into full bloom. (And here’s a fun fact: During rehearsals one of her dance numbers was not working exactly right, so producers Alex A. Aarons and Vinton Freedley asked a dancing star they knew to step in and refine the choreography as a favor, and he coached Ginger on the routine in the lobby of the Alvin during rehearsals. You guessed it: It was Fred Astaire.)

Playing Girl Crazy‘s lead was 19-year-old Ginger Rogers, fresh from making her Broadway debut in Top Speed and creating a sensation purring “Cigarette me, big boy” in her first movie, Young Man of Manhattan. She had two of Girl Crazy‘s most enduring songs, “Embraceable You” and “But Not for Me”, and by all accounts handled them quite nicely. But lacking what Cole Porter later called Ethel Merman’s “golden foghorn” voice, she had to stand helplessly by while Ethel stole her thunder night after night; it would take the intimacy of the movie camera to coax her star into full bloom. (And here’s a fun fact: During rehearsals one of her dance numbers was not working exactly right, so producers Alex A. Aarons and Vinton Freedley asked a dancing star they knew to step in and refine the choreography as a favor, and he coached Ginger on the routine in the lobby of the Alvin during rehearsals. You guessed it: It was Fred Astaire.)Rounding out the principal cast of Girl Crazy were its two nominal stars, comedians Willie Howard and William Kent, and juvenile lead Allen Kearns. (Understand, “juvenile” was a relative term in the theater of the day, denoting a romantic character type rather than age; think Dick Powell with Ruby Keeler. In fact, Kearns was 37, old enough to be Ginger Rogers’s father).

Act II finds half the population of Custerville in San Luz. Danny finds Molly, bids her farewell and wishes her all the best with Sam; only after he leaves does she realize her true feelings for him, and now she fears the knowledge has come too late. But when she learns that Sam has registered them at the local hotel as husband and wife, she realizes what a cad he is and runs to Danny’s arms. Outraged, Danny blurts a threat against Sam that returns to bite him when Sam is assaulted and robbed and Danny is accused of the crime. Meanwhile, Kate confronts her cheating husband. Eventually — jeez, let’s cut to the chase — Gieber exposes Lank and his henchman Pete as the men who robbed Sam, Kate and Slick reconcile, Danny and Molly are reunited, and everybody presumably lives happily ever after back in Custerville.

Act II finds half the population of Custerville in San Luz. Danny finds Molly, bids her farewell and wishes her all the best with Sam; only after he leaves does she realize her true feelings for him, and now she fears the knowledge has come too late. But when she learns that Sam has registered them at the local hotel as husband and wife, she realizes what a cad he is and runs to Danny’s arms. Outraged, Danny blurts a threat against Sam that returns to bite him when Sam is assaulted and robbed and Danny is accused of the crime. Meanwhile, Kate confronts her cheating husband. Eventually — jeez, let’s cut to the chase — Gieber exposes Lank and his henchman Pete as the men who robbed Sam, Kate and Slick reconcile, Danny and Molly are reunited, and everybody presumably lives happily ever after back in Custerville.To be continued…

Crazy and Crazier, Part 2

I have this fantasy in which I imagine that a scout from RKO Radio Pictures early in 1931 is told to go see Girl Crazy on Broadway and to report back about its potential as a movie. In his report, does he say, “The score is amazing; George and Ira Gershwin have written some songs that will be sung as long as singers sing”? Or “This Ethel Merman is dynamite; she electrifies an audience and she can put a song over like an artillery barrage”? Or “Ginger Rogers is a real charmer who has already shown that she photographs well; with care she could be groomed into a major star”? Does he say any of this? He does not. Instead, this brilliant showbiz oracle tells the front office, “This might make a good vehicle for Wheeler and Woolsey.”

I have this fantasy in which I imagine that a scout from RKO Radio Pictures early in 1931 is told to go see Girl Crazy on Broadway and to report back about its potential as a movie. In his report, does he say, “The score is amazing; George and Ira Gershwin have written some songs that will be sung as long as singers sing”? Or “This Ethel Merman is dynamite; she electrifies an audience and she can put a song over like an artillery barrage”? Or “Ginger Rogers is a real charmer who has already shown that she photographs well; with care she could be groomed into a major star”? Does he say any of this? He does not. Instead, this brilliant showbiz oracle tells the front office, “This might make a good vehicle for Wheeler and Woolsey.”

Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey — unlike, say, Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, or the Marx Brothers — are largely forgotten today, but they still have their fans among film buffs even now. So perhaps I should let you know right up front that Wheeler and Woolsey are my personal nominees for the worst comedy team in movie history. But no matter what I think, they were hugely popular in the 1930s. Their output alone shows that audiences could hardly get enough. The Marx Brothers, for example, made 13 pictures in their entire career, from 1929 to ’49. Wheeler and Woolsey made 22 features — plus one short of their own and guest appearances in five others — just between 1929 and ’37. And they only stopped then because of Woolsey’s failing health (he died of kidney failure at 50 in 1938).

Wheeler and Woolsey were never a team in the standard showbiz sense of the day, as Woolsey was careful to point out when the two split up (briefly) after the release of Girl Crazy in 1932: “I wish it understood that Wheeler and I never really formed a team at any time. He had his manager and attorney and I had mine.” Wheeler had started in vaudeville with an act that, in retrospect, sounds like a forerunner of Andy Kaufman’s schtick: he would come out on stage with a joke book and announce that he was going to read some jokes from it, then proceed to read one corny joke after another, in such a manner that the audience would wind up roaring with laughter. Woolsey, who stood just under five foot six, had started out as a jockey and exercise boy, but when he broke his leg in a fall from a horse his racing career was over. The horse, Pink Star, went on to win the Kentucky Derby in 1907; Woolsey went into show business.

Bringing the two together was Florenz Ziegfeld Jr.’s idea; he cast them as comic supports to Ethelind Terry and J. Harold Murray in his 1927 musical extravaganza Rio Rita. When RKO bought the movie rights to Rita in 1929, they replaced the stars with John Boles and Bebe Daniels, but they brought Wheeler and Woolsey west to recreate their stage roles. The dynamic of this duo was already firmly in place, and it would not vary in their following match-ups: wide-eyed naif Wheeler is bamboozled and manipulated by the fast-talking, cigar-chomping Woolsey. The two made such a hit in Rita that RKO teamed them up again (The Cuckoos) and again (Dixiana), over and over — a new picture, on average, every three months. (“They were pretty bad,” Wheeler later recalled, “but they all made money.”) Girl Crazy was their tenth, in two-and-a-half years.

Almost a third member of the (not really a) team was diminutive Dorothy Lee; she appeared in 16 of Wheeler and Woolsey’s pictures. A good physical match for Wheeler (he was five foot four, she five foot exactly), Lee served as a romantic partner for him, giving Wheeler (and the audience) a little relief from the obnoxious blowhard Woolsey. So it was in Girl Crazy, in which Wheeler took the role played on Broadway by Willie Howard (whose intransigence had killed the show before its time). The cabbie’s name was de-ethnicized from Gieber Goldfarb to Jimmy Deegan, the character was divested of the comic Yiddish persona that was Howard’s stock in trade, and Lee was brought in as Patsy, “the gal of the golden west”, to duet with Wheeler in one of only four musical numbers in the movie.

Almost a third member of the (not really a) team was diminutive Dorothy Lee; she appeared in 16 of Wheeler and Woolsey’s pictures. A good physical match for Wheeler (he was five foot four, she five foot exactly), Lee served as a romantic partner for him, giving Wheeler (and the audience) a little relief from the obnoxious blowhard Woolsey. So it was in Girl Crazy, in which Wheeler took the role played on Broadway by Willie Howard (whose intransigence had killed the show before its time). The cabbie’s name was de-ethnicized from Gieber Goldfarb to Jimmy Deegan, the character was divested of the comic Yiddish persona that was Howard’s stock in trade, and Lee was brought in as Patsy, “the gal of the golden west”, to duet with Wheeler in one of only four musical numbers in the movie.

Musicals, a novelty in the late ’20s, had worn out their welcome by 1932 and become a drug on the market; theater owners were known to reassure audiences in ads and posters that their current offering was “Not a Musical!” (The Big Revival over at Warner Bros. was still a year away.) In this atmosphere, no one at RKO was in a mood to look twice at the Gershwins’ songs in Girl Crazy. Instead, taking their cue from Willie Howard and William Kent having been the ones with star billing on Broadway, the studio jettisoned most of the score and refashioned the book — the weakest thing about the show — to suit their hot new team. So it is that in the movie, it isn’t Eddie Quillan’s Danny Churchill who takes a taxi from Manhattan to Arizona, it’s the gambler Slick (new surname: Foster) who hops into Jimmy Deegan’s cab for the trip out west. (The lady in the back seat with Woolsey is Kitty Kelly, playing what’s left of Ethel Merman’s role.) Two huge chunks of the picture’s modest 74-minute running time are eaten up by (1) Wheeler and Woolsey’s misadventures on the road to Arizona and (2) further misadventures later, when the action adjourns to Mexico.

Musicals, a novelty in the late ’20s, had worn out their welcome by 1932 and become a drug on the market; theater owners were known to reassure audiences in ads and posters that their current offering was “Not a Musical!” (The Big Revival over at Warner Bros. was still a year away.) In this atmosphere, no one at RKO was in a mood to look twice at the Gershwins’ songs in Girl Crazy. Instead, taking their cue from Willie Howard and William Kent having been the ones with star billing on Broadway, the studio jettisoned most of the score and refashioned the book — the weakest thing about the show — to suit their hot new team. So it is that in the movie, it isn’t Eddie Quillan’s Danny Churchill who takes a taxi from Manhattan to Arizona, it’s the gambler Slick (new surname: Foster) who hops into Jimmy Deegan’s cab for the trip out west. (The lady in the back seat with Woolsey is Kitty Kelly, playing what’s left of Ethel Merman’s role.) Two huge chunks of the picture’s modest 74-minute running time are eaten up by (1) Wheeler and Woolsey’s misadventures on the road to Arizona and (2) further misadventures later, when the action adjourns to Mexico.  As for those four songs, only three were from the show. The movie opens promisingly with an amusing, if abbreviated, rendition of “Bidin’ My Time”, with four singing cowboys moseyin’ along on the back of the same overburdened horse, while the camera moves through the Custerville cemetery from the grave of one luckless sheriff to the next, and the next.

As for those four songs, only three were from the show. The movie opens promisingly with an amusing, if abbreviated, rendition of “Bidin’ My Time”, with four singing cowboys moseyin’ along on the back of the same overburdened horse, while the camera moves through the Custerville cemetery from the grave of one luckless sheriff to the next, and the next. A few minutes later comes “You’ve Got What Gets Me” a new song by George and Ira written for the movie. (In point of fact, it wasn’t entirely new; it was a reworking of another song, “Your Eyes, Your Smile”, which had been cut from the Broadway production of Funny Face before it opened in 1927.) This is a light romantic duet between Wheeler and Dorothy Lee (already, as noted, a staple of their pictures together), followed by a sprightly tap dance in which they’re joined by little Mitzi Green as Wheeler’s pesky sister. Toward the end of her life, Dorothy Lee remembered Girl Crazy with bitter disgust as the movie where they photographed her behind a post (“I saw it once,” she said. “I couldn’t look at it again.”), and this frame from the dance shows she wasn’t being hypersensitive — you can just about make out her elbows (she’s dancing to the left of Wheeler). Why would anybody bother to stage a tap dance on a set dominated by an enormous vine-covered wishing well right in the middle of the floor (and seemingly taking up half of it)? It’s hard to comprehend — but then, the songs simply weren’t a priority.

A few minutes later comes “You’ve Got What Gets Me” a new song by George and Ira written for the movie. (In point of fact, it wasn’t entirely new; it was a reworking of another song, “Your Eyes, Your Smile”, which had been cut from the Broadway production of Funny Face before it opened in 1927.) This is a light romantic duet between Wheeler and Dorothy Lee (already, as noted, a staple of their pictures together), followed by a sprightly tap dance in which they’re joined by little Mitzi Green as Wheeler’s pesky sister. Toward the end of her life, Dorothy Lee remembered Girl Crazy with bitter disgust as the movie where they photographed her behind a post (“I saw it once,” she said. “I couldn’t look at it again.”), and this frame from the dance shows she wasn’t being hypersensitive — you can just about make out her elbows (she’s dancing to the left of Wheeler). Why would anybody bother to stage a tap dance on a set dominated by an enormous vine-covered wishing well right in the middle of the floor (and seemingly taking up half of it)? It’s hard to comprehend — but then, the songs simply weren’t a priority.  But, with all due sympathy to Ms. Lee, that’s not the worst. The absolute nadir of RKO’s Girl Crazy — lower than any of Wheeler and Woolsey’s comedy, already too low by half — comes with the disgraceful treatment accorded “But Not for Me”. What on Broadway had been a wistful solo of lost love by Ginger Rogers was revamped as a trio for Eddie Quillan as Danny, Arline Judge as Molly, and Mitzi Green trying to patch things up between them. Ira’s lyric was twisted around to say the exact opposite of what he wrote (“Beatrice Fairfax, don’t you dare/Ever tell me he won’t care…”), and George’s tempo was sped up until the song sounded like the merry-go-round gone wild in Strangers on a Train. Quillan and Judge were hardly singers (which may explain the breakneck tempo, always easier for non-singers to handle), and they rush through the song as if they have to be someplace; Quillan darts off-camera before the music even tinkles to a stop. The song comes off like a playground argument between two petulant kids. It’s followed by a reprise in which Green tries to cheer Judge up by using the song to do impressions (and pretty good ones, too) of Bing Crosby, Roscoe Ates, George Arliss and Edna May Oliver. This plays oddly today, especially with audiences who never heard of Ates, Arliss or Oliver, but at least it had a counterpart in the original show: Willie Howard was famous for his impressions, and the book incorporated them by having the cabbie try to cheer Ginger Rogers’ Molly with a reprise a la Rudy Vallee and Maurice Chevalier — but only after Ginger had already given the song its full soulful due. This movie never bothers to do that.

But, with all due sympathy to Ms. Lee, that’s not the worst. The absolute nadir of RKO’s Girl Crazy — lower than any of Wheeler and Woolsey’s comedy, already too low by half — comes with the disgraceful treatment accorded “But Not for Me”. What on Broadway had been a wistful solo of lost love by Ginger Rogers was revamped as a trio for Eddie Quillan as Danny, Arline Judge as Molly, and Mitzi Green trying to patch things up between them. Ira’s lyric was twisted around to say the exact opposite of what he wrote (“Beatrice Fairfax, don’t you dare/Ever tell me he won’t care…”), and George’s tempo was sped up until the song sounded like the merry-go-round gone wild in Strangers on a Train. Quillan and Judge were hardly singers (which may explain the breakneck tempo, always easier for non-singers to handle), and they rush through the song as if they have to be someplace; Quillan darts off-camera before the music even tinkles to a stop. The song comes off like a playground argument between two petulant kids. It’s followed by a reprise in which Green tries to cheer Judge up by using the song to do impressions (and pretty good ones, too) of Bing Crosby, Roscoe Ates, George Arliss and Edna May Oliver. This plays oddly today, especially with audiences who never heard of Ates, Arliss or Oliver, but at least it had a counterpart in the original show: Willie Howard was famous for his impressions, and the book incorporated them by having the cabbie try to cheer Ginger Rogers’ Molly with a reprise a la Rudy Vallee and Maurice Chevalier — but only after Ginger had already given the song its full soulful due. This movie never bothers to do that.As it happened, the final cut wasn’t final after all. Girl Crazy had begun under the regime of RKO studio chief William LeBaron; by the time it finished shooting, LeBaron was gone (though he retained screen credit), replaced by David O. Selznick. The picture’s first preview in Glendale was not well received, and Selznick ordered retakes — enough to add another $200,000 to the $300,000 already spent. Exactly what was reshot isn’t clear, but the figures alone suggest a full two-thirds of the picture as it stood. In any case, director William A. Seiter wasn’t available, so the retakes were directed (without credit) by Norman Taurog.

And this is where we run into the mystery of the “I Got Rhythm” number. Selznick may have ordered the reshooting of the song, in whole or in part (the paper trail isn’t clear), and the sequence may have been staged and directed by Busby Berkeley, who was already at RKO to stage the native dances for Bird of Paradise. Berkeley himself never said anything about it, but that doesn’t necessarily mean anything — after all, Dorothy Lee didn’t like to talk about Girl Crazy either, and she’s on screen. On the strength of what we can see, my own opinion is that “I Got Rhythm” is Busby Berkeley’s work lock, stock and barrel. Later, after Berkeley had made his name over at Warner Bros., dance directors at other studios would prove that Berkeley’s style was easier to recognize than to imitate, and “I Got Rhythm” is his style to a “T”; there are images and motifs that would reappear in some of his most famous routines at Warners. Besides, this number is by far the most elaborate and complex sequence in the entire picture, and could easily account for much of that extra 200 grand. Until someone shows me conclusive evidence to the contrary, I’ll continue to believe that “I Got Rhythm” is Busby Berkeley at work. Whatever the case, Berkeley, like Taurog, got no screen credit for the retakes Selznick had ordered.

The retakes didn’t help, and may have hurt; Girl Crazy failed to turn a profit. After Selznick’s tinkering, it had cost nearly twice as much as the typical Wheeler and Woolsey picture (and almost as much as RKO’s special-effects extravaganza King Kong); it never had a chance. It probably never had an artistic chance either; coming at exactly the moment when even mentioning a musical around Hollywood was in bad taste, Girl Crazy was a movie that couldn’t decide what it wanted to be. It waffled a little, then came down on what looked like the safe side as a straight cornball comedy. RKO decided to play up the one feature of the show (the book) that Broadway audiences had tolerated only for the sake of what came with it, leaving just a skeleton crew of songs that were either inconsequential, mishandled, or too little too late.

The following year would come the game-changer: Warner Bros. (and Busby Berkeley) with the spectacular hat trick of 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade to put musicals back in vogue again, where they would remain for decades — even Poverty Row studios like Republic, Monogram and PRC would regularly try their hands at them. But all that came too late to help RKO’s Girl Crazy. It was born before its time; the studio didn’t appreciate the property it had, and didn’t have the wit, confidence or foresight to do what should have been done with it.

The following year would come the game-changer: Warner Bros. (and Busby Berkeley) with the spectacular hat trick of 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade to put musicals back in vogue again, where they would remain for decades — even Poverty Row studios like Republic, Monogram and PRC would regularly try their hands at them. But all that came too late to help RKO’s Girl Crazy. It was born before its time; the studio didn’t appreciate the property it had, and didn’t have the wit, confidence or foresight to do what should have been done with it.

All was not lost, however. Better times were coming for Girl Crazy, though it would take another 11 years. Oddly enough, Norman Taurog and Busby Berkeley would be back. And this time they’d get screen credit.

Crazy and Crazier, Part 3

By the time Girl Crazy came to the screen again, Hollywood’s attitude toward musicals had changed diametrically, and with a will. A look at Clive Hirschhorn’s comprehensive coffee-table book The Hollywood Musical tells the tale: 10 musicals in 1932, when the first woebegone movie of Girl Crazy came out, versus 50 of them in 1942, the year MGM decided to do it again, and 75 in 1943, when MGM’s Girl Crazy was released. By now, musicals had become the jewels in Hollywood’s crown. Even Universal’s remake of The Phantom of the Opera had more opera and less phantom than the original silent version with Lon Chaney (sound gave Universal some wiggle room, and they decided to fill it with singing).

By the time Girl Crazy came to the screen again, Hollywood’s attitude toward musicals had changed diametrically, and with a will. A look at Clive Hirschhorn’s comprehensive coffee-table book The Hollywood Musical tells the tale: 10 musicals in 1932, when the first woebegone movie of Girl Crazy came out, versus 50 of them in 1942, the year MGM decided to do it again, and 75 in 1943, when MGM’s Girl Crazy was released. By now, musicals had become the jewels in Hollywood’s crown. Even Universal’s remake of The Phantom of the Opera had more opera and less phantom than the original silent version with Lon Chaney (sound gave Universal some wiggle room, and they decided to fill it with singing).

MGM bought the rights to Girl Crazy from RKO in 1939 at the behest of producer Jack Cummings. Cummings’s original idea was to remake the movie as a vehicle for Fred Astaire and Eleanor Powell, which presumably would have shifted the emphasis back to the songs and been more in keeping with the original show. Anyhow, nothing ever came of that, but Cummings held on to the property for several years. In the meantime, his MGM colleague Arthur Freed had produced a number of successful musicals, including three teaming Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland: Babes in Arms (’39), Strike Up the Band (’40) and Babes on Broadway (’41).

In mid-1942, Freed had designer-director John Murray Anderson, musical director Johnny Green, costumer Irene Sharaff and swimming starlet Esther Williams all under contract to develop a vehicle for Williams, but a workable script had never materialized and the project remained on a back burner. So Freed went to Cummings and proposed a swap: the whole Esther Williams package for the rights to Girl Crazy as a vehicle for Mickey and Judy. Cummings liked the idea, so did Louis B. Mayer, and the thing was done. (Cummings later produced Bathing Beauty, Esther Williams’s first starring picture.) Girl Crazy went into production in January 1943 with Busby Berkeley (who had directed the three previous Mickey-and-Judy musicals) directing.

Today, Arthur Freed is considered synonymous with “MGM musicals”, as if he were the only musical producer on the lot. Not so; there were also Cummings and Joe Pasternak (who had moved over from Universal, where he built his name on Deanna Durbin’s pictures), and both got their share of the glory at the time. Still, Freed’s unit was an awfully well-oiled machine, and Freed had a knack for attracting the best talent and getting the best out of it. His production of Girl Crazy reunited two men with a nostalgic stake in doing the thing right: Roger Edens and Georgie Stoll, both of whom had come far since their days in the orchestra pit of Girl Crazy on Broadway. (I wonder: Had Stoll and Edens seen RKO’s 1932 Girl Crazy and been appalled?) Now, Stoll would be credited as musical director on the picture; Edens’s credit reads “Musical Adaptation”, but that hardly scratches the surface of what Edens really did. As I said before, he was Freed’s right-hand man, much more than a “musical adaptor”, and on Girl Crazy he was virtually what would later be called a line producer — the guy actually on the set keeping an eye on things for the man in charge (i.e., Freed). And there was trouble almost immediately.

The first sequence Berkeley shot was the “I Got Rhythm” production number, which was originally planned to come about three-fourths of the way through the picture, and Edens didn’t like what he saw. “I’d written an arrangement of ‘I Got Rhythm’ for Judy,” Edens recalled, “and we disagreed basically about its presentation. I wanted it rhythmic and simply staged, but Berkeley got his big ensembles and trick cameras into it again, plus a lot of girls in Western outfits with fringed skirts and people cracking whips and firing guns all over my arrangement and Judy’s voice. Well, we shouted at each other and I said there wasn’t enough room on the lot for both of us.” (Edens exaggerated somewhat; there were no gunshots going off over Garland’s vocals. Otherwise, he has a point; the number begins to sound like the gunfight at the O.K. Corral.)

Berkeley’s working relationship with Judy Garland was unraveling as well. This was the fifth movie he directed her in — there had been For Me and My Gal (’42) in addition to the three with Rooney — and under his martinet bullying her attitude had gone from “I don’t know what I’d do without him” (on For Me and My Gal) to “I used to feel he had a big black bullwhip and was lashing me with it” (in conversation with Hedda Hopper, reported in Hopper’s autobiography). Judy was close to hysterics on the set of “I Got Rhythm”, her nervousness heightened by a stunt Berkeley designed in which she and Mickey were hoisted aloft by the ankles. The bit terrified Judy, just as a similar hoisting had when Berkeley put her through it in the “Minnie from Trinidad” number in Ziegfeld Girl (’40) — this time, making things worse for her, the bit was accompanied by dozens of pistols firing over and over again around her. After “I Got Rhythm” was in the can, Judy’s personal physician ordered her not to dance for three weeks.

To put the icing on the cake, Berkeley took nine days to shoot the number instead of the scheduled five, and he ran $60,000 over its budget.

So let’s recap: After less than two weeks, Girl Crazy was four days behind schedule and 60 grand over budget. Judy Garland was frazzled, Roger Edens was furious. Obviously, Berkeley had to go. Freed removed him from the picture and replaced him with Norman Taurog.

So let’s recap: After less than two weeks, Girl Crazy was four days behind schedule and 60 grand over budget. Judy Garland was frazzled, Roger Edens was furious. Obviously, Berkeley had to go. Freed removed him from the picture and replaced him with Norman Taurog.

The movie dispensed with all that nonsense about the $742.30 cab ride, but it still had playboy Danny Churchill (Rooney) making a spectacle of himself in New York. “Treat Me Rough” was the song used, performed by Tommy Dorsey’s band and sung by June Allyson. (Allyson was an MGM newcomer, simultaneously filming this one-shot while recreating her Broadway role in the studio’s movie of Best Foot Forward. By the time Girl Crazy was released, she had already made her splash in Best Foot Forward and was on her way to major stardom.)

This time, Danny’s a college student as well as a tycoon’s playboy son, and Dad (Henry O’Neill) cancels his return to Yale and sends him to his own alma mater “out west” (Cody College, the state unspecified). There, under the eye of Cody’s dean (Guy Kibbee), he is the usual fish out of water, smitten with the dean’s grandaughter, postmistress Ginger Gray (Judy). (I wonder: was the changing of the heroine’s first name a wink to Broadway’s original Molly, Ginger Rogers? How could it not be?)

From there Girl Crazy becomes a variation on the hey-kids-let’s-put-on-a-show formula that framed all the Mickey-and-Judy musicals, the variation this time being hey-kids-let’s-put-on-a-rodeo-and-save-the-school-from-closing. The plot is within hailing distance (just barely) of Bolton and McGowan’s original book, but it’s beside the point anyway, as it was on Broadway. In 1943, with Hollywood in general, and the Freed Unit at MGM in particular, operating at an all-time peak of efficiency and self-confidence, Girl Crazy was then what it remains today: an exhilarating series of musical highlights, one after another, bathing the screen in an embarrassment of riches. Clive Hirschhorn’s succinct appraisal is oft-quoted because it’s the plain truth: “Gershwin never had it so good.”

At the risk of becoming monotonous, let us count the ways. First, of course, is that rambunctious version of “Treat Me Rough”, which June Allyson invests with an innocent tomboy eroticism (she’s like a less obnoxious Betty Hutton) that must have had the Hays Office wondering if this sort of thing was really okay, then shrugging and deciding it was all just good clean fun after all.

At the risk of becoming monotonous, let us count the ways. First, of course, is that rambunctious version of “Treat Me Rough”, which June Allyson invests with an innocent tomboy eroticism (she’s like a less obnoxious Betty Hutton) that must have had the Hays Office wondering if this sort of thing was really okay, then shrugging and deciding it was all just good clean fun after all.

The quirky love-hate duet “Could You Use Me?” was something that Eddie Quillan and Arline Judge actually might have handled pretty well if RKO had deigned to include it in 1932. But they didn’t, and it was left to Mickey and Judy to bring it to the screen. Filmed in punishing 112-degree heat on location on a desert road outside Palm Springs (with pickup shots in the relative comfort of a soundstage back in Culver City), it’s a cheerful charmer in which Judy manages to suggest that Ginger’s resistance to Danny’s brash advances is already beginning to melt.

The quirky love-hate duet “Could You Use Me?” was something that Eddie Quillan and Arline Judge actually might have handled pretty well if RKO had deigned to include it in 1932. But they didn’t, and it was left to Mickey and Judy to bring it to the screen. Filmed in punishing 112-degree heat on location on a desert road outside Palm Springs (with pickup shots in the relative comfort of a soundstage back in Culver City), it’s a cheerful charmer in which Judy manages to suggest that Ginger’s resistance to Danny’s brash advances is already beginning to melt. “Embraceable You” is presented at a party for Ginger, in a scene that includes the movie’s only non-Gershwin interpolation: a chorus of “Happy Birthday to You” from Cody College’s assembled student body. Judy sings to the boys, then dances with them all, one by one and in groups, with an extended pas de deux with dance director Charles Walters. Later, after graduating to full direction himself, Walters helmed Judy in Easter Parade (’48), Summer Stock (’50), and her triumphant one-woman show at Broadway’s Palace Theatre in 1951.

“Embraceable You” is presented at a party for Ginger, in a scene that includes the movie’s only non-Gershwin interpolation: a chorus of “Happy Birthday to You” from Cody College’s assembled student body. Judy sings to the boys, then dances with them all, one by one and in groups, with an extended pas de deux with dance director Charles Walters. Later, after graduating to full direction himself, Walters helmed Judy in Easter Parade (’48), Summer Stock (’50), and her triumphant one-woman show at Broadway’s Palace Theatre in 1951. When Danny Churchill attends a party at the Governor’s Mansion to lobby against the closing of Cody, he meets up with his old pal Tommy Dorsey, and that sets the stage for a nifty piece of Big Band Era history: Tommy Dorsey and his Orchestra in a marvelous pop-concert rendition of “Fascinating Rhythm”. It’s a jumpin’ arrangement, and features a solo by “Danny Churchill” on piano. In fact, Mickey Rooney’s playing was dubbed by Arthur Schutt; still, as his keyboard fingering in the scene makes clear, Rooney was an accomplished pianist himself, and to the end of his days he spoke of the thrill of getting to perform “Fascinating Rhythm” with Dorsey and his band. (No doubt, even though the number had been prerecorded on MGM’s music stage, the band — including guest soloist Rooney — played for real on the set.)

When Danny Churchill attends a party at the Governor’s Mansion to lobby against the closing of Cody, he meets up with his old pal Tommy Dorsey, and that sets the stage for a nifty piece of Big Band Era history: Tommy Dorsey and his Orchestra in a marvelous pop-concert rendition of “Fascinating Rhythm”. It’s a jumpin’ arrangement, and features a solo by “Danny Churchill” on piano. In fact, Mickey Rooney’s playing was dubbed by Arthur Schutt; still, as his keyboard fingering in the scene makes clear, Rooney was an accomplished pianist himself, and to the end of his days he spoke of the thrill of getting to perform “Fascinating Rhythm” with Dorsey and his band. (No doubt, even though the number had been prerecorded on MGM’s music stage, the band — including guest soloist Rooney — played for real on the set.) That party leads to the inevitable misunderstanding when Ginger believes Danny has returned to his girl-crazy ways with the governor’s daughter (Frances Rafferty). It all gets sorted out in time for a happy ending, natch, but not before Judy Garland gets the opportunity — Hallelujah! — to redeem the tawdry vandalism of “But Not for Me” back in 1932. This is not only the high point of Girl Crazy — it’s the high point of Judy Garland’s entire career. With all due respect to “Over the Rainbow”, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”, “The Man That Got Away” or anything else you care to name, this is Judy’s best. Co-star Gil Stratton talked about watching the number being shot and said “it was something you ought to have paid admission to see.” The simplicity of Taurog’s staging, the delicate cinematography of William Daniels, and the combined artistry of Judy and and the Gershwin brothers all fuse into the kind of magic that the Hollywood of 1943 had led audiences to take for granted. Judy Garland was as good as it got, then or ever after, and here’s the proof.

That party leads to the inevitable misunderstanding when Ginger believes Danny has returned to his girl-crazy ways with the governor’s daughter (Frances Rafferty). It all gets sorted out in time for a happy ending, natch, but not before Judy Garland gets the opportunity — Hallelujah! — to redeem the tawdry vandalism of “But Not for Me” back in 1932. This is not only the high point of Girl Crazy — it’s the high point of Judy Garland’s entire career. With all due respect to “Over the Rainbow”, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”, “The Man That Got Away” or anything else you care to name, this is Judy’s best. Co-star Gil Stratton talked about watching the number being shot and said “it was something you ought to have paid admission to see.” The simplicity of Taurog’s staging, the delicate cinematography of William Daniels, and the combined artistry of Judy and and the Gershwin brothers all fuse into the kind of magic that the Hollywood of 1943 had led audiences to take for granted. Judy Garland was as good as it got, then or ever after, and here’s the proof. Originally, Girl Crazy was to end with a reprise of “Embraceable You”, Mickey and Judy surrounded by the rest of the cast as the orchestra swells up and out. But Busby Berkeley’s flamboyant staging of “I Got Rhythm”, scheduled to come almost 20 minutes before the end, threatened to turn anything that followed into a dribbling anticlimax. There was some hurried reshuffling of the script and music, and Girl Crazy as it was released on November 26 ended with “I Got Rhythm”. It must have positively galled Roger Edens; he’d gotten his way and had Berkeley canned from the picture, and now here was Berkeley literally getting the last word — cracking whips, blazing six-guns and all. But it was the right call, and, however grudgingly, Edens probably had to admit it.

Originally, Girl Crazy was to end with a reprise of “Embraceable You”, Mickey and Judy surrounded by the rest of the cast as the orchestra swells up and out. But Busby Berkeley’s flamboyant staging of “I Got Rhythm”, scheduled to come almost 20 minutes before the end, threatened to turn anything that followed into a dribbling anticlimax. There was some hurried reshuffling of the script and music, and Girl Crazy as it was released on November 26 ended with “I Got Rhythm”. It must have positively galled Roger Edens; he’d gotten his way and had Berkeley canned from the picture, and now here was Berkeley literally getting the last word — cracking whips, blazing six-guns and all. But it was the right call, and, however grudgingly, Edens probably had to admit it.

Crazy and Crazier, Part 4

The 1960s were, in a literal if not a figurative sense, a golden age for movie musicals; they made more money (a total of over $250 million, real money back then — about $2.128 billion today) and won more awards (four best picture Oscars, best director for each one, 34 Oscars in the various craft categories, plus a more-than-respectable smattering of acting awards and nominations) than they ever had before or would again. There were West Side Story, Gypsy, The Music Man, Bye Bye Birdie, The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, Mary Poppins, Thoroughly Modern Millie, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, Half a Sixpence, Funny Girl, Oliver!…

The 1960s were, in a literal if not a figurative sense, a golden age for movie musicals; they made more money (a total of over $250 million, real money back then — about $2.128 billion today) and won more awards (four best picture Oscars, best director for each one, 34 Oscars in the various craft categories, plus a more-than-respectable smattering of acting awards and nominations) than they ever had before or would again. There were West Side Story, Gypsy, The Music Man, Bye Bye Birdie, The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, Mary Poppins, Thoroughly Modern Millie, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, Half a Sixpence, Funny Girl, Oliver!…

But there were also Babes in Toyland, Star!; Doctor Dolittle; Camelot; The Happiest Millionaire; Goodbye, Mr. Chips; Hello, Dolly!; Paint Your Wagon; Darling Lili; On a Clear Day You Can See Forever…huge (even bloated), expensive productions that contributed to that quarter-billion box office, but not enough to turn a profit for themselves.

There were other signs that, literal golden age or not, the figurative Golden Age (the real one) had passed. The industry had spent the entire 1950s staggering from the double blows of the advent of television and the U.S. Justice Department’s antitrust suit that broke up Hollywood’s efficient production/distribution/exhibition system. Desperate to balance the books, studios sharply curtailed or even eliminated the infrastructure that made musicals (always an expensive proposition) at least viable on a regular basis: music departments, rosters of contract players, specialty acts, in-house writers, orchestrators, dancers and dance directors. At MGM, for example, the Arthur Freed, Jack Cummings and Joe Pasternak units all withered on the vine. Freed produced his last musical, Bells Are Ringing, in 1960, and it barely broke even; after two more non-musicals (The Subterraneans and Light in the Piazza) he had pretty much retired. (He nursed a forlorn hope through the late ’40s, ’50s and early ’60s of producing Say It With Music, an epic biopic of Irving Berlin’s life and songs, to no avail.)

Tastes in popular music had also changed, and Hollywood’s old guard, though game to try, was ill-equipped to cope. In a metaphorical but very real sense, Hollywood was torn between West Side Story and The Sound of Music on one hand, and Jailhouse Rock and A Hard Day’s Night on the other.

It was in this atmosphere, right smack in the middle of the decade, that Girl Crazy emerged in its third and final screen incarnation. It was planned as a vehicle for pop chanteuse Connie Francis. Her popularity was just beginning to wane under the onslaught of the Beatles-led British Invasion, but we can see that only in retrospect; at the time she seemed as popular as ever. And she was very popular indeed — the first female to have two consecutive number one hits (“Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool” and “My Heart Has a Mind of Its Own” in 1960) and the youngest entertainer to headline in Las Vegas and at New York’s Copacabana (that same year). Also in 1960, Francis made her screen debut in MGM’s Where the Boys Are (and had another big hit with the title tune). It was the custom in those days, when a singer had a hit song, to make the follow-up single as much like the hit as possible, so MGM and Francis followed Where the Boys Are with Follow the Boys. And that’s why, when the studio decided to revamp Girl Crazy for Connie Francis, the show got a new title (and a new song for Connie to croon): When the Boys Meet the Girls.

It was in this atmosphere, right smack in the middle of the decade, that Girl Crazy emerged in its third and final screen incarnation. It was planned as a vehicle for pop chanteuse Connie Francis. Her popularity was just beginning to wane under the onslaught of the Beatles-led British Invasion, but we can see that only in retrospect; at the time she seemed as popular as ever. And she was very popular indeed — the first female to have two consecutive number one hits (“Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool” and “My Heart Has a Mind of Its Own” in 1960) and the youngest entertainer to headline in Las Vegas and at New York’s Copacabana (that same year). Also in 1960, Francis made her screen debut in MGM’s Where the Boys Are (and had another big hit with the title tune). It was the custom in those days, when a singer had a hit song, to make the follow-up single as much like the hit as possible, so MGM and Francis followed Where the Boys Are with Follow the Boys. And that’s why, when the studio decided to revamp Girl Crazy for Connie Francis, the show got a new title (and a new song for Connie to croon): When the Boys Meet the Girls. Connie’s co-star was Harve Presnell, a veteran of the opera and concert stage who had made a splash on Broadway in The Unsinkable Molly Brown, then won a Golden Globe for the movie version opposite Debbie Reynolds. At that stage of his career he was tall and handsome, with a lush baritone voice — a slightly younger, blonde version of Howard Keel. But his timing couldn’t have been worse: By 1965 not even Keel was getting enough work to keep him busy; he hadn’t made a musical since Kismet in 1955, and had segued into straight acting roles. Presnell would have a tougher time of that; as a screen actor he was a little stiff, without Keel’s comfort in front of a camera. He made one more major movie, stealing Paint Your Wagon from Clint Eastwood and Lee Marvin with his rendition of “They Call the Wind Maria”, then it was back to regional theater and Broadway tours until he returned to movies as a character actor in his 60s and 70s. Things worked better for him then; the stiffness that had looked a bit wooden in his youth seemed more like patrician dignity in his senior years, and he had a distinguished second career in movies (Fargo, Saving Private Ryan, Flags of Our Fathers, Evan Almighty) before dying of pancreatic cancer at 75 in 2009.

Connie’s co-star was Harve Presnell, a veteran of the opera and concert stage who had made a splash on Broadway in The Unsinkable Molly Brown, then won a Golden Globe for the movie version opposite Debbie Reynolds. At that stage of his career he was tall and handsome, with a lush baritone voice — a slightly younger, blonde version of Howard Keel. But his timing couldn’t have been worse: By 1965 not even Keel was getting enough work to keep him busy; he hadn’t made a musical since Kismet in 1955, and had segued into straight acting roles. Presnell would have a tougher time of that; as a screen actor he was a little stiff, without Keel’s comfort in front of a camera. He made one more major movie, stealing Paint Your Wagon from Clint Eastwood and Lee Marvin with his rendition of “They Call the Wind Maria”, then it was back to regional theater and Broadway tours until he returned to movies as a character actor in his 60s and 70s. Things worked better for him then; the stiffness that had looked a bit wooden in his youth seemed more like patrician dignity in his senior years, and he had a distinguished second career in movies (Fargo, Saving Private Ryan, Flags of Our Fathers, Evan Almighty) before dying of pancreatic cancer at 75 in 2009.First of all, there was what we shall charitably call the movie’s “creative team”. They were, almost to a man (and they were all men), a gaggle of second-rate hacks — from producer Sam Katzman through director Alvin Ganzer and writer Robert E. Kent to musical director Fred Karger. Katzman has a handful of memorable “B” titles (It Came from Beneath the Sea, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers), some low-camp legends (Rock Around the Clock, Cha-Cha-Cha Boom!) and a couple of lesser Elvis Presley vehicles on his shoddy resume, but by and large, we’re slumming even to mention his name. Ganzer directed only two features besides this one — The Girls of Pleasure Island (’53) and Three Bites of the Apple (’67) — in a career devoted almost exclusively to undistinguished piecework on this or that TV series.

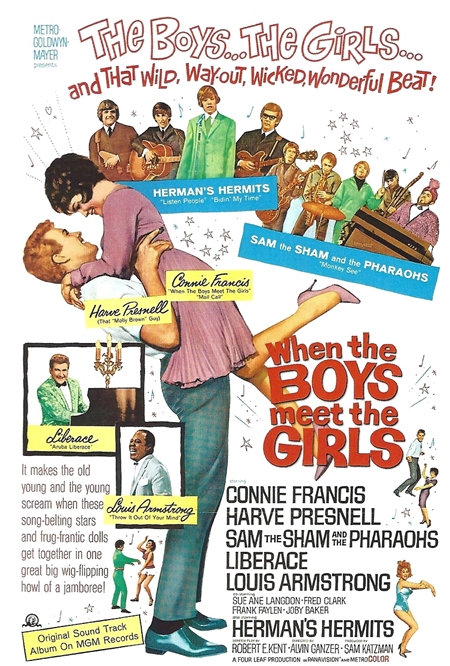

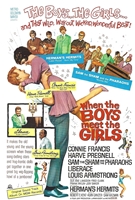

In addition to the mediocrity (and less) of the men in charge — and perhaps because of it — When the Boys Meet the Girls has the air of a movie that simply doesn’t know why it is being made, who its target audience is, or even what it is selling. For example, compare the three posters with which I began my post on each Girl Crazy picture:

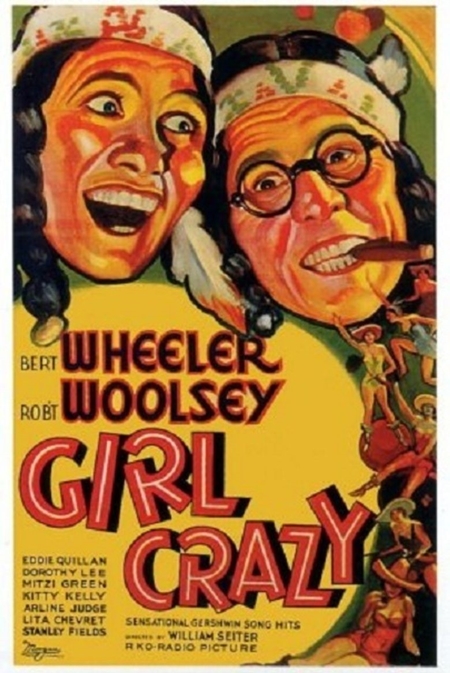

The poster for Girl Crazy (1932) knows exactly what it’s selling: For better or for worse (and it seemed like a good idea at the time), the big draw is Wheeler and Woolsey; their faces and names dominate the graphics completely, suggesting hilarity unrestrained.

It’s the same with Girl Crazy (1943): Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, and a bonus plug for Tommy Dorsey and his band, with a cartoon bucking cow (a cow??) offering the promise of a barrel of rollicking fun.

Now When the Boys Meet the Girls. I’ve reproduced each poster small, deliberately, to show that for the ’32 and ’43 posters the main idea still comes through. But with this one you can barely even make out the title.

Now give your eyes a break and scroll back up to the larger version of the When the Boys poster. Can you even guess what that poster is selling? Herman’s Hermits? Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs? Or what? Connie and Harve get top billing (under the title), and two figures meant to represent them dominate the poster, more or less, but only in closed-off profiles that barely resemble them; Presnell’s image doesn’t look like him at all. And did you notice that oh-so-fab blurb in the lower left corner? “It makes the old young and the young scream when these song-belting stars and frug-frantic dolls get together in one great big wig-flipping howl of a jamboree!” Good grief. Are we ready to howl and flip our wigs?

And say, how about that lineup of featured acts? Did you ever imagine you’d see them all together in one place? Besides Connie and Harve to carry the boy-meets-wins-loses-and-wins-girl-back plot, you have…

…Herman’s Hermits, with special “Also Starring” billing, no less. Here they’re singing “Listen, People”, which was one of their hits, and the only hit to come out of the movie that wasn’t already a Gershwin standard. Peter Noone (“Herman”) even had a few lines of dialogue, and the Hermits also delivered “Bidin’ My Time”. But more on that later; for now, back to the lineup…

Seriously, can’t you just smell the sweaty desperation behind this kind of programming? This isn’t a vaudeville or a variety show, it’s Sam Katzman and his minions throwing everything they can think of at the screen, all the while hoping to God someting will stick.

Does any of it stick? Well, Liberace is a hoot, for starters. But there are other rewards on hand. Both Harve Presnell and Connie Francis have a quite creditable go at “Embraceable You” — starting with Harve, on the occasion of Danny Churchill first setting eyes on the winsome Ginger…

…then later Connie, on a moonlit night after Ginger has gotten to know Danny and started to fall for him.

Later still, after the usual misunderstanding — this time prompted by the arrival of Danny’s gold-digging ex-girlfriend Tess Raleigh (Sue Ane Langdon) — Harve and Connie do very nicely indeed on “But Not for Me”. It’s a sort of separate duet with each taking a verse, first Ginger in her bedroom, then Danny in his, then the two together, joined by a split screen — the movie’s one creative use of the Panavision frame. True, Connie Francis and Harve Presnell don’t measure up to Judy Garland on either of these songs, but there’s no shame in that — nobody could. On both numbers, Connie and Harve are in their element and entirely at ease; as a result, their performances of the songs are simple, heartfelt and effective. Liberace’s number may be the most fun in When the Boys Meet the Girls, but “Embraceable You” and “But Not for Me” are the most Gershwin. If you saw only the clips of these two songs, you would come away with the impression that When the Boys Meet the Girls is a lot better than it really is.

Things get a bit rockier when Connie and Harve launch into “I Got Rhythm” — here, as in 1932, the movie’s one major production number. Once again, they sing “I’ve Got Rhythm” — an annoyance, but a recurring one where this song is concerned. More troublesome this time is the pace and style of the number, a laid-back, casual approach that tries for a kind of ring-a-ding hipster cool, like Frank Sinatra in his finger-snapping-loose-collar-narrow-tie-sportcoat-slung-over-the-shoulder phase. No disrespect to Old Blue Eyes, but it doesn’t exactly make for a dynamic musical delivery:

“I’ve [beat! beat!] got rhy-(beat!)-thm (beat! beat!)…”

So naturally, the boys…

…and the girls take over the dancing chores. There’s nothing wrong with any of this, exactly, but it’s too self-consciously smooth and loosey-goosey to whip up any excitement on the wide screen. The number is like something pulled together in a few days to back up a guest star on The Andy Williams Show. You find yourself longing to hear Tommy Dorsey and his blaring, driving brass and to see Busby Berkeley’s caffeinated choristers with their whips, guns and stomping military precision.

This lackadaisical rendition of “I Got Rhythm” brings us to the man who was probably the most resolutely third-rate personage involved with When the Boys Meet the Girls. His name was Fred Karger, and his on-screen credit is “Music Scored and Conducted By”. Karger had spent years in the music department at Columbia Pictures making hardly a ripple; his biggest coup to date had been writing the tune for “Gidget”. On When the Boys Meet the Girls, besides scoring and conducting, he wrote the song “Mail Call” (with Ben Weisman and Sid Wayne), which did not add to Connie Francis’s string of hits.

It’s safe to assume that Sam the Sham, Louis Armstrong and Liberace all tended to their own music without any interference, so Karger’s work here probably boils down to the treatment of the five Gershwin songs. He neither helped nor hindered Connie and Harve with his arrangements of “Embraceable You” and “But Not for Me”, and his pointless rewriting of “Treat Me Rough” didn’t keep Sue Ane Langdon from squeezing a little fun out of it with her kitten-with-a-whip delivery. Otherwise, Karger was careless, even downright sloppy.

I’ve already mentioned Karger’s mushy, low-watt arrangement of “I Got Rhythm”, which offered scant inspiration to choreographer Earl Barton and his dancers. Karger was also careless with Ira Gershwin’s lyrics, beyond the addition of that “ve” to the title of “I Got Rhythm”; he fiddled with almost every line Ira wrote, either killing the rhyme (“There’s no regrettin’/When I’m set-ting“) or killing the sense (changing “Although I can’t dismiss the memory of her kiss” to “And yet I can’t dismiss” in “But Not for Me”) time and time again — then repeating the mistake, as if to prove he did it on purpose.

But one of Karger’s bright ideas really takes stupidity to undreamed-of heights, and that’s in his treatment of “Bidin’ My Time”. The number is given to Herman’s Hermits, sitting on and around a flatbed truck while the rest of the young cast gets busy building Ginger’s dude ranch. At first things seem to go well with the song: it’s an almost witty idea, handing this lazy cowboy lullaby to these slightly nerdy lads from Manchester. Peter Noone’s wispy tenor voice slides nicely into the verse, then the refrain moves into a ricky-ticky soft-samba rhythm similar to the Beatles’ version of “Till There Was You”. Then, trouble. Now as just about everybody but Fred Karger and Peter Noone knew by 1965, the song is supposed to go like this:

But one of Karger’s bright ideas really takes stupidity to undreamed-of heights, and that’s in his treatment of “Bidin’ My Time”. The number is given to Herman’s Hermits, sitting on and around a flatbed truck while the rest of the young cast gets busy building Ginger’s dude ranch. At first things seem to go well with the song: it’s an almost witty idea, handing this lazy cowboy lullaby to these slightly nerdy lads from Manchester. Peter Noone’s wispy tenor voice slides nicely into the verse, then the refrain moves into a ricky-ticky soft-samba rhythm similar to the Beatles’ version of “Till There Was You”. Then, trouble. Now as just about everybody but Fred Karger and Peter Noone knew by 1965, the song is supposed to go like this:“I’m bidin’ my ti–ime

‘Cause that’s…the kinda guy I–I’m…”

But no. Instead we get:

“I’m biding my ti–ime

‘Cause that’s…the kind of guy I…am…”

If there is such a thing as lyrical tone-deafness, this is surely it. It not only kills the rhyme, it kills the whole joke of the song. It’s like that old comedy routine of the clueless singer tackling the Gershwins’ “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off” for the first time: “You say ee-ther, and I say ee-ther / You say nee-ther, and I say nee-ther…” Only here it is, so to speak, with a straight face. After that clunker, nothing Herman or the Hermits can do will save the song; we just have to cringe our way through to the end. The bumbling Fred Karger was as far from Roger Edens and Georgie Stoll as anyone could get and still be able to read music (assuming Karger could); this proves it.

On that sour note I’ll close this look at When the Boys Meet the Girls. As I said, the picture’s not a total loss, thanks to the talents of Connie Francis and Harve Presnell, plus a certain amount of blind monkeys-and-typewriters luck. Twenty years earlier, both Connie and Harve might have left a stronger legacy. Especially Connie; with the guidance of a Roger Edens, and with more directors like Henry Levin and Richard Thorpe (on her first two pictures) and fewer like Alvin Ganzer (on this one), she might have had the nurturing that Doris Day got over at Warner Bros., and might have made more than the four movies she did (When the Boys Meet the Girls was her last). Harve would still have had to contend with Howard Keel, but there was room for a deep talent pool at MGM in the ’40s and early ’50s. By the time Harve showed up in 1964, or even Connie in 1960, the support system just wasn’t there, and their clear talent didn’t get the attention it needed and deserved.

* * *

Well, friends, there you have it, just as I promised at the beginning of this series — the full arc of the Golden Age of the Hollywood Musical, encapsulated in the fortunes of one legendary Broadway show:

Girl Crazy (1932) was the product of a time when musicals looked passe, so the deathless Gershwin score was shouldered aside to make room for a brand of cornball comedy that looked like the coming thing. But the musical was poised on the cusp of a Great Revival; the talent was present and in good working order, though it hadn’t found its footing yet, and the techniques that would make the Hollywood musical something distinctly different from its Broadway cousin were still being discovered and developed.

A scant third-of-a-century later came When the Boys Meet the Girls — a movie not without talent, but with a vacuum behind the scenes — and at mighty MGM, no less. Arthur Freed may have retired broken by disappointment, but Jack Cummings and Joe Pasternak were still active, as were Roger Edens, Georgie Stoll, and directors like Vincente Minnelli, Stanley Donen, Charles Walters, George Sidney. You get what you pay for, and MGM wasn’t willing to pay for them; what they were willing to pay for was a gang of humdrum nonentities who didn’t know what they were doing — and that’s what they got. It was as if Freed, Edens, Cummings, Pasternak et al. had cleaned out their offices, tucking the studio’s only copies of How to Make a Movie Musical into their briefcases before turning out the lights and locking the door.

But in between those two — that was a whole other story. The stars (in every sense of the word) were perfectly aligned, and the final product could hardly miss because it was designed not to miss. Designed by producer Arthur Freed, who had come to movies with sound and stretched his producer’s muscles first on The Wizard of Oz; designed by Roger Edens and Georgie Stoll, who had been with the show on Broadway and knew in their bones and fingertips the vitality of the Gershwin score; designed by Busby Berkeley, who had jump-started the Golden Age and still knew a trick or two, whether Roger Edens liked it or not. And it was designed for Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, just about the most talented individuals who ever faced a camera. Girl Crazy (1943) was what happened when the factory’s machinery was all in place and well-tended: The vehicle came off the line humming like a top, and if it had to fly, it soared.