The Museum That Never Was, Part 1

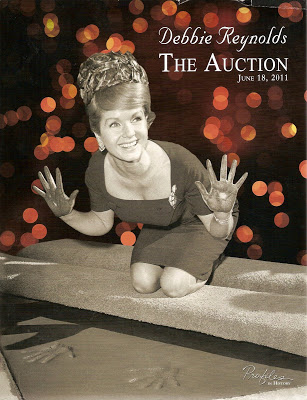

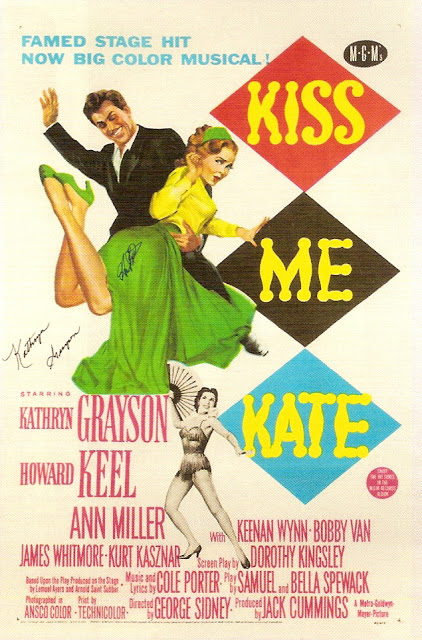

When I bought the catalog for the Debbie Reynolds Auction from the Profiles in History auction house, I admit it was with the thought that I just might be able to get down to L.A. for the event itself on June 18. Well, family plans closer to home made that idea a non-starter, but there was still the possibility that I might be able to bid on something by phone or on line. Then a 16mm print came up for auction on eBay that I set my cap for, and it wound up costing more than I expected, though less than I was willing to pay. (Not that you asked, but it’s a kinescope of a 1956 live TV dramatization of Jim Bishop’s The Day Lincoln Was Shot starring Raymond Massey, Lillian Gish and Jack Lemmon.)

So what with one thing and another, my hopes of getting to the auction or of taking home anything from it were not to be.

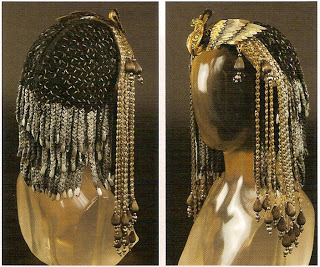

other hand, if you were daunted by the

$30,000 opening bid, or by the headdress’s

fragile condition…

I’m not sure what Debbie’s vision for her museum was; myself, I’d have loved to see something like the Gene Autry Western Heritage Museum — now known as the Autry National Center — in Griffith Park. (And by the way, if you thought a “Gene Autry Museum” would amount to little more than a collection of Gene’s old guitars and posters from his movies, think again. It’s a world-class facility honoring every facet of America’s western heritage, and belongs at the top of your must-see list if you’re ever in Los Angeles.) Whatever Debbie’s ideas were, they’ve come to naught, while she’s spent half her life (and apparently all her money) acquiring and properly storing and maintaining umpteen thousand pieces of Hollywood history — and trying to find a home for them.

Frankly, if I were Debbie Reynolds, I’d be mad enough to bite the bumper off a truck. In an interview about the auction with Idaho TV station KIDK, she said, with an air of philosophical resignation, “I’m a fan of all of these great stars and I wanted to save their moment for a museum for the future. I didn’t reach that goal, which makes me sad, but these things will be shared with people that love the stars as much as I do.” In another interview she sounded a little more like I’d probably feel (i.e., testier): “I am really sick and tired of it. I feel that I must call it a day now. Over the years, I have literally spent millions of dollars protecting it and taking care of it. If you were me, wouldn’t you give up after 35 years? There is no other road. I need a little rest from the responsibility of trying to do something it seems that nobody else wants to do. Hopefully everyone will have a good time with their piece.”

All those years haven’t completely gone to waste. The day-to-day operations of Golden Age Hollywood are as over and done as the haggling in an Etruscan marketplace. We may still have the movies — and that ain’t exactly nothin’ — but it won’t do to lose sight of the nuts and bolts that went into building them. Being able to see and study these artifacts (like this gown Debbie wore as she crooned “A Home in the Meadow” in How the West Was Won) gives them a real-world texture and solidity that the movies alone, even HTWWW in all its 7-channel Cinerama glory, could never do.

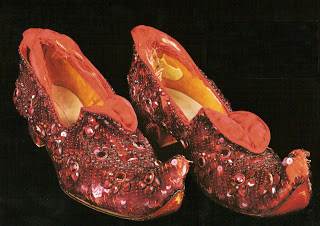

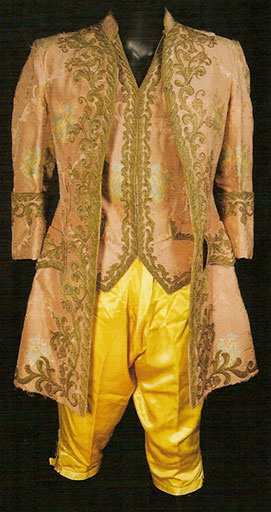

Without Debbie Reynolds, the items in her collection — Charlie Chaplin’s derby, Basil Rathbone’s Sherlock Holmes Inverness cape, Audrey Hepburn’s black-and-white Ascot dress (and Rex Harrison’s clash-matching brown suit), Barbra Streisand’s entire Funny Girl wardrobe, the kids’ drapery outfits and Julie Andrews’s guitar from The Sound of Music, Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra sedan chair, palace decorations and Yul Brynner’s whip from The King and I, Bette Davis’s throne from The Virgin Queen, Empress Josephine’s royal bed from Desiree, Clifton Webb’s Boy Scout uniform from Mr. Scoutmaster, Howard Keel’s rifle from Annie Get Your Gun (or Clark Gable’s from Mogambo), the 20-foot miniature warships from The Winds of War, the Ark of the Covenant from David and Bathsheba — all might well be long-moldering somewhere in Los Angeles County’s bulging landfills. As frustrated and disappointed as Debbie might be, she can claim victory in (and we can thank her for) having shepherded all these things past the point where they were simply junk.

I’ll have more to say on this in Part 2…

The Museum That Never Was, Part 2

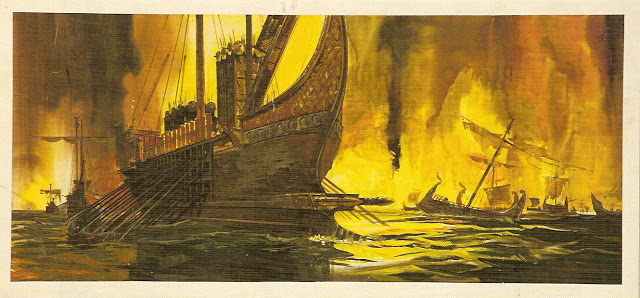

The good news about the Debbie Reynolds Auction is that there was an auction at all. She saved all these items from oblivion, and now they’re around for us to see. Debbie’s main interest was in the costumes, but there’s plenty of other stuff in her collection, like this concept painting from the 1963 Cleopatra. Just to illustrate how things can change from the early concept stages to final production…

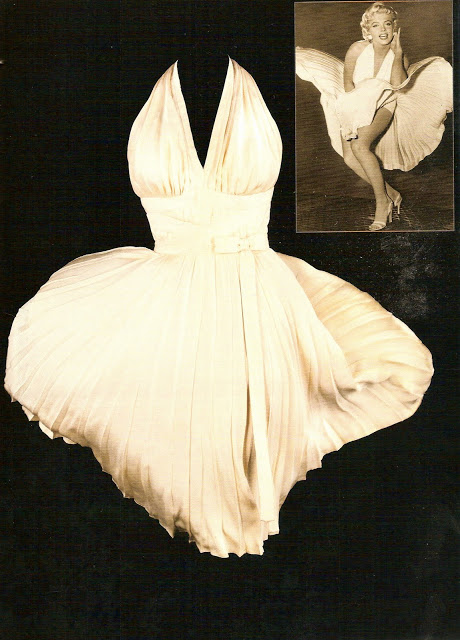

Now that Debbie is relinquishing her stewardship, we can reasonably assume that, whoever may wind up with this or that individual piece, the collection as a whole is safe for the forseeable future; nobody pays $5 million for a dress if they’re planning to leave it wadded up on the bottom shelf of the linen closet, or set it out on the curb next time the Salvation Army truck comes around. But where are the pieces going, and what precisely is going to become of them? Collectors can be a secretive and territorial bunch, not always quick to share. (And who can blame them? There are a lot of unscrupulous people out there; see here for a mention of the mysterious fate of Marcel Delgado’s production photos from The Lost World [’25] and King Kong [’33].) In the auction catalogue from Profiles in History, there’s a special plea from London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, asking for the loan of certain items in the collection for an exhibit on Hollywood costumes planned for October 2012 through January 2013. Debbie had promised curator Deborah Nadoolman Landis the use of any costumes she wanted — until the need to sell torpedoed the arrangement; it’ll be interesting to see if any of the new owners come through for the V&A.

So the Debbie Reynolds Collection existed in the first place, and it’s (most likely) safe now; that’s the good news. The bad news is that it won’t be a collection anymore. True, last month’s auction was only 587 lots out of whatever (5,000? 10,000?) is the total. Does Debbie intend to sell only enough to pay her outstanding debts, then start again at Square One with what’s left? Perhaps, but she certainly sounds as if she’s in the process of washing her hands of the whole kit and kaboodle. That’s perfectly understandable, but it’s still a shame.

I’ll miss having the opportunity to wander through the halls of the Debbie Reynolds Hollywood Movie Museum, and to go back as often as time and resources would allow; I suspect a single day wouldn’t have been enough to see it all. It’s comforting to know that these things are in the hands of people who’ll appreciate them, but having them all together in one place would have made the museum so much greater than the sum of its parts. As Virginia Postrel says, “To understand the past you need a large sample. Only then can you separate idiosyncratic variation from broad trends.”

I hinted at this idea in Part 1, when I suggested mix-and-matching a Cleopatra costume from the 1930s, ’40s and ’60s. How instructive it would have been to compare costumes from the 1925 and ’59 versions of Ben-Hur; or Mutiny on the Bounty ’35 and ’62; or how Adrian dressed Charles Boyer as Napoleon in Conquest (’37) vs. how Rene Hubert and Charles LeMaire dressed Marlon Brando in Desiree.

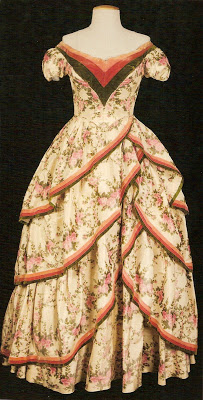

Or take this shot of Katharine Hepburn as Mary of Scotland (1936). You can see Mary of Scotland any time you like, and maybe you have. But while you were taking in the lavish settings and costumes captured by Joseph August’s richly atmospheric, deeply shadowed black-and-white cinematography, did it ever occur to you that the gown Kate is wearing here…

…really looked like this? We enter so completely into the world of any black-and-white movie (and arguably, Mary of Scotland is not one of the best) that we tend to forget that anyone ever thought of them in terms of color. We think, perhaps, that the studios wouldn’t spend money on something the camera wouldn’t see. But think that one through: The actors would see it. If Katharine Hepburn’s costume had really been composed of the shades of black and gray that we see on screen and in the picture above, she would surely have acted differently than she did in this sumptuous red and gold garment. And the camera would certainly have seen that.

This is one of the things I most noticed in looking through the costumes in the catalogue, the striking variety of color in costumes and set pieces built for black-and-white movies. That gold gown from DeMille’s Cleopatra is another example; it may look silver on screen, but no, it was gold.

If you’re interested in a catalogue of your own, you can (at least as of this date) order it here from Profiles in History. If you don’t want to pay the $39.95 — and don’t mind not getting the quality high-gloss paper it’s printed on — you can even download the catalogue for free on PDF. But be warned: It’s 312 pages and will probably take quite a while to download (and even longer to print), and it’ll probably take up quite a chunk of your hard drive when it gets there.